Haunted MTL Original – Queen of Crows – Holly Baker

More Videos

Published

5 years agoon

By

Shane M.“Queen of Crows” by Holly Baker

Arnold pocketed the dark phone and flicked the butt of his glowing cigarette to the asphalt, crushing it under a loose boot beside a dried snake skin. Flattened by a tire, most likely. Not much living out here. Nothing worth much, anyway. A solitary bird flew high overhead, marring the otherwise uninterrupted azure of midday, and a dust-colored cricket jumped onto his shoulder and away again, into the sun-crisped grasses; but the one was just passing through and the other just a remnant of plague. Arnold didn’t count that as life.

He pushed himself off the car-side door and came around to the front. The phone’s battery might have been dead, but the car’s was not, so it was time to choose, and as far as he was concerned, the choice was obvious: head up and to the trees. But Erasmo, leaning over the Rand McNally he’d spread open on the golden hood of his Tío’s prized Studebaker, was less resolute. His finger was planted on a curving red line that cut through the center of the page where he believed they had stopped. Meanwhile, he twisted his head from map to horizon, to the left and to the right, trying to make sense of the twisty roads and endless hills.

The car was already beginning to stink, and if they hung around much longer, they would attract more than just these damn crickets. His patience fully sapped, Arnold smacked the hood of the car, and Erasmo jumped. An argument ensued, as it always did. Erasmo wanted to have done with it, turn around, go back the way they came. The tank was half drained already, he said, and they couldn’t afford any more highway meandering. That was why the hills were their best bet. But Arnold wanted it done right, and for that, they needed the cover of trees. As he always did, Arnold prevailed.

They piled back into the Studebaker, and Erasmo turned the key in the ignition with a prayer on his lips. After winning it in a game of roulette and painting it the color of pirate gold in his garage, Erasmo’s Tío had christened the jalopy El Dorado. Besado por el Sol, he also named it, and Dientes del Abuelito. Despite all the work he’d put into it, the car still ran as though it had loose bolts in the engine. But if, when Tío got out of the crowbar hotel, there was so much as a dimple in the fender or a hairline crack in the paint, it would be Erasmo’s ass under the wheels. The engine spluttered and groaned to be put back to work, but work it did, and they rolled back onto the asphalt.

For his part, Arnold had no tíos, no tías, no nada de familia. So, he didn’t know what it was like to have the fear of God drilled into his bones and stamped onto his heart. To be fair, it took a healthy dose of imagination to start with, to assume he even had a heart.

Only five mile-markers later, at the crest of the next rise, they spotted her: a lone sojourner walking in their same direction on the shoulder on the opposite side of the road. At first, she appeared to be just a large, stuffed backpack with long, bare, willowy legs ending in a pair of high-ankle hiking boots. But hearing the wobbly roar of the jalopy, she turned, revealing a petite girl nearly half the size of the pack that loomed over her. She wore a pair of jeans cut short at the crotch line. Above the belt hung a sleeveless army-green tank atop which rested a heavy, circular pendant. A pink paisley kerchief kept her bristly black hair out of her eyes, and on both wrists were a dozen woven bracelets of every color, defying the insipid desert palette. The buckle straps from the backpack crossed her breasts and hips to ease her heavy load, as the hiker’s backpack extended well over her own head and swayed as she turned and, spotting them, stuck out her thumb for a ride.

Another rushed argument followed. This was an opportunity, Arnold said, so slow down and let’s have a chat. In answer, Erasmo put his foot on the gas and sped up. Again, Arnold hissed at the tocapelotas to stop the damn car so they could talk to her, and smacked Erasmo in the ear. As before, Arnold won, and Erasmo rolled to a stop beside the extended thumb.

She met them at the open window, where she grasped the gold door, bent at the waist, and cocked her head to see them. Nice wheels, she said, a thing she would have said to any double axles with the good nature to stop for a stranger. Erasmo shrugged, unengaged, and kept his nose pointed at the road. For his part, Arnold leaned across to the driver’s window, pushed his mirror glasses a little further down his nose so she could see his pretty blue eyes, and smiled to show off his new sparkly white caps. Her own gleamed in response, even though the sun was hiding its face from behind a brushing of wispy white clouds.

They’re yours, he said, and wherever she was meant to be, he promised to take her there. This baby was El Carro de la Reina, and did she know what it meant? She shook her head and he answered with a wink: the Queen’s Carriage.

Before she could ask if he was sure, before she could even say thank you, he was out of the car and passing around the hood to where she was unclipping the straps of her pack, up top and down low. He eased the straps down from her shoulders and escorted her around to the passenger’s side, where he pulled open the door and the seat forward so she could hop in the back.

The pack was heavier than it looked, which was saying something of its bearer, with her limbs like aspens: long, white, thin and sturdier than they appeared, and lined with horizontal scars. From one zipper hung a Zippo lighter keychain, from another a pink tube of pepper spray that could be mistaken for lipstick. The pockets were covered with patches: a four-leaf clover, a Canadian flag, a Route 66 road sign, and a red heart framing the words All You Need Is Love. Arnold refrained from an eyeroll.

It was a tight fit already in the Studebaker’s boxy trunk, so some rearranging was required. After lifting out a pair of dusty shovels, Arnold shoved the twin glittering turquois heels further to the back, creating just enough room to wedge the pack. Then replaced the shovels, and the lid fell shut with a loud clunk.

When he looked up, he caught sight of Erasmo’s disapproving eyes in the rearview mirror. Arnold just scratched his nose with a middle finger, nonchalant as all hell, and ran two hands through his hair to slick it back. He returned to the passenger’s seat.

Her name was Ava, she said, though Arnold suspected this it was not her real name, but one she had chosen for herself. He also doubted her age. Twenty-two, she claimed, but Arnold didn’t put her a day over eighteen. Still, he kept silent as she spun her tale and declared herself a nomad, ever since running away from home, just to get out from under the same roof as her mother and her mother’s boyfriend, who thought he was as good as her father, and who had tried to ground her for coming home past midnight and for smoking weed in her own bedroom. He touched her, too. Nothing awful or invasive, not like some girls got from their mothers’ boyfriends, but unwanted all the same—light pinches and pats and pets, and always while her mother was in the room, and never did her mother ever say a word. But she put up with it. That was, she said, until the day the bastard hit her. She hit the road after that, didn’t think twice. She called it he best decision of her life.

And such a short life at that, Arnold thought. Did she realize? He readjusted his estimate: sixteen, maybe.

Sorry, said Ava, they didn’t need to know all of that. A million stories like hers, she said. Erasmo shrugged, but Arnold empathized: The world was filled with nasty men. Ava was more generous: But some good ones, too. She meant Arnold and Erasmo.

Arnold rolled his head, regarding her in the backseat from head to bare knees from behind his mirror glasses. Her ears were studded with faux-silver hoops. The pendant was a pewter Celtic knot. Her nails were painted black. Great ink work, said Arnold, touching his own wrist to indicate hers, where the tattoo of a crow in flight spanned from ulna to radius, poking above the bracelets. She had another, perched on a branch on her collarbone, and probably a third, where they couldn’t see but Arnold suspected was there all the same. Girls her age. Predictable.

Los cuervos son mala suerte, muttered Erasmo. Arnold flicked him in the ear to punish him, then angled himself toward the backseat to ask Ava whether she spoke Spanish. She didn’t, so he interpreted: He says crows are good luck. She smiled. It was a beautiful smile, the kind only people who trusted people could make.

He showed her his, too: the marijuana leaf, its ribs tracing the prominent bones of the back of his left hand; the clock on the side of his neck, its hands set at 8:44; the tally marks running up his arm, numbering nine.

She asked what they meant, touching her own neck to indicate his, her own arm. He laid a finger on his neck and said, Instruction. His hand trailed down to his arm and said, Reminder. Then he winked cryptically. He asked, Yours?

I’m Queen of Crows, she said, returning the wink. He laughed, and so did she. Only Erasmo’s lips remained straight, his jaw tight. His hands, curled around the wide steering wheel, tightened until the leather squeaked. He really was such a spoil sport.

Erasmo here’s sore she hadn’t asked about his, Arnold said to excuse his friend’s rudeness. He pointed to the back of Erasmo’s neck, where a decorative Christian cross extended from the hairline just behind his ear down to the meat of his shoulder. He had about a dozen of them, he explained to Ava: Erasmo was the superstitious sort.

He had always been so, at least as far as Arnold knew, ever since the murder of his father in cold blood and the inter-family war that followed. A bloody affair, the way Erasmo told it, which he only ever had, once, long ago, one long night, plied with alcohol and bemoaning the fact that he really couldn’t stand the sight of blood.

He had been just nine when it all went down, but his tío had taken him to the garage anyway, on the outskirts of the pueblo, pressed a gun to his hand, and pointed him up a tree with the instruction to matar al diablo. Why? Because justice comes from above, his tío said, pointing to the sky, then lifting the silver cross around his neck and kissing it. That day, he told his nephew, with a meaty hand clapping his shoulder, Erasmo would become justice. So the boy climbed the tree and sat among the birds. Not long after, while his tío and cousins stood waiting, the others arrived in two shiny black trucks, six or seven men, Erasmo couldn’t remember. But among them was the man who had murdered his father. They faced one another, spoke together, but Erasmo, too far away, heard nothing, not until the blast of a gun scared the birds from the trees and the first man fell.

From his spot, hidden in the crook of a tree limb, Erasmo watched as each of the bad men and two of his cousins were shot down. Watched, and did nothing. The gun was little more than a prayer book in his hands. Later, his tío called him gallina, a coward, too weak to avenge his own father. For the next ten years, he dragged Erasmo up and down the countryside to teach him what it was to deliver justice from above.

By the time Arnold came knocking on his door, looking for a driver, Erasmo was a grown man and hardened by the things he had seen and done. He had twelve tattoos, twelve crosses, but it was unclear whether they were prayers for forgiveness, or shields against the devil. Superstitious indeed. Arnold knew they were neither. Just dark ink on sun-darkened skin.

To save the moment, Ava leaned forward, resting her folded arms on the seat in front of her and grinning at Erasmo. She liked his tattoos, she said. They were a kind of good luck charm all their own, weren’t they? His eyes darted to her once in the rearview mirror, then fixed themselves again on the road.

The sky seemed to dim the higher they climbed. Or maybe it was that the trees were growing taller, or closer together. There was no clock on the dash of the Studebaker, and of course his dead phone couldn’t tell the time, but surely sunset was still many hours away, which should have pleased Erasmo somewhat, even as his gas needle sank steadily toward E. All right, he had tortured the old boy long enough. And so, without turning his head from the side window or lifting his sunglasses from his nose, Arnold said they were far enough, and to leave the road and turn into the trees. Erasmo pulled the wheel, squeezing El Dorado between a gap in the pines.

Ava said nothing, not at first. Perhaps she thought they were turning around, or parking to take a piss, but as they rolled slowly through the woods, cutting their own trail the width of the Studebaker, she asked why they had left the road, and what they were doing.

The car rumbled deeper into the woods, pitching them gently to and fro. Arnold assured her it wouldn’t take long, but would she indulge them while they took care of a little business matter? Again, he flashed her his contagious smile. Though she seemed less certain than before, she smiled anyway and nodded. It was no longer the smile of one who trusted.

When Arnold said so, Erasmo stopped the jalopy and killed the engine with the resignation of one who doubted it would ever start again. The men exited the car. They didn’t invite her out. So, she waited in the backseat, feigning composure, but alert to every sigh and shiver of the trees.

Outside the car, Arnold stretched his back. Cracked his neck. Rolled his shoulders. Then, he began to whistle. He joined Erasmo at the trunk of the car and popped open the golden lid like it was a treasure chest. First, they pulled out the oversized backpack and set it on the ground. Then Erasmo lifted the two shovels. At last, Arnold grabbed the turquois heels, twisted them around, and dragged them out so they hung over the lip of the trunk.

His tune ended, and he whistled sharply. Inside the car, Ava turned her head in answer. He beckoned her with a friendly wave and called her to join them. There was a moment’s hesitation as she inclined her head to the window, trying to see up and out, trying to make sense of what was happening. Then she was decided. She crawled to the front seat then out the side door, and as she walked around the side, Erasmo, holding his shovels, moved aside, to stand at her back, and wait for the signal, should it come.

When she saw the legs draping from the trunk, she gasped and froze. Arnold expected it. Flight would come next, once the initial shock wore off, and he was ready for that, too. Fight was the least likely, not for this one. But then Ava surprised him.

She asked the name of the woman in the trunk. The men exchanged glances, and as Erasmo choked up on the handles of the shovels resting on his shoulder like baseball bats, Arnold answered with the casual concern of one remarking on disappointing weather: Connie or Callie or Corrie, he wasn’t sure. She asked what had happened to her, and Arnold answered that she hadn’t known where she was going. She asked, finally, had it been a world filled with nasty men, and Arnold answered yes.

Finally, she turned toward Erasmo and extended her arm for a shovel. She would help dig, she said, and lay Connie or Callie or Corrie to rest.

And so they dug, taking turns and sharing two shovels among the three of them. The ground below was soft, but a web of roots slowed their progress. Erasmo proposed that shallow was good enough, but Arnold that deeper was better. Fit for two bodies, not one. That was what he meant. Ava, bless her, said nothing at all.

A breeze cooled the sweat on their foreheads and ruffled the leaves overhead, casting the forest floor in pale dappled sunlight. At the same time, the woods were darkening as if dusk had come early. Can’t be that late yet, Arnold thought, and didn’t remove his sunglasses. There was still some ways to go. He relieved Ava of a shovel and told her to fetch a flashlight from the trunk while he took her place in the hole. As he planted the shovel further into the earth, he heard, from a short distance, Ava apologizing softly to the dead woman as she rummaged beneath her body in search of the Coleman flashlight. She found it and returned, shining the light into the hole while she rested on a fallen log.

Perhaps the hole was already deep enough, but Arnold didn’t stop, and so neither did Erasmo. Tonight, he would earn his tenth tally mark. A little ahead of schedule, but hell, he thought, needs must when the devil drives. Then he heard the sharp caw of a crow.

It seemed out of place in the forest, this high up in the mountains. Not that Arnold knew much about birds and their habitats. But he had adapted to the silence that seemed to follow in his wake. Or was it that he always walked deadened trails? Either way, the bird was an intruder. Because there it was, appearing suddenly, perched on the Studebaker like a shiny, black hood ornament, its head twitching sharply here and there, as though curious about the scene before it, two men burrowing into the earth and a woman lighting their way.

Erasmo scowled and made to climb out of the hole, to startle it away, when Ava begged him not to. He stilled, one leg out of the hole. Crows were good luck, she reminded him, echoing Arthur’s translation. He laughed unkindly at her misunderstanding and glared at Arnold for his deceit. Erasmo didn’t like games, never had. If Arnold was a cat with a mouse between its paws, playing a game of catch-and-release, Erasmo was the snake that that sprang with fangs already drawn. A snake shouldn’t have to pay deference to a cat. But they both knew why he did.

Didn’t they know, Ava continued, that crows were keepers of women’s secrets? Had they not grown with the story? She thought everyone knew. She turned up her wrist, exposing the tattoo, and told them a story.

Once, there was a woman who loved a man very much. But the man had a black heart, and a deceptive spirit. Deceived by his tongue, clever like a snake’s, and his charm, warm like a bear’s, she ignored the warnings of her mother and father and ran away with him. He took what he wanted from her, alone in the woods, where none could see, only the birds—swallows and robins and crows. When he drew his knife, she screamed, and the sound of her screams entered into the crows. The other birds took flight, but the crows stayed to witness.

Later, after the man had fled, her mother and father and all the townspeople went in search of her. For days, they searched, and for days they ignored the cawing of the crows—such an unpleasant, unmusical noise they did not wish to hear. But finally, they listened, and they followed the crows into the woods, to the spot where he had buried her. Only then—as though a radio had been tuned from static to station—did they hear the woman’s voice in the throats of the crows and know that it had been the lost woman all along, yearning to be found.

It was an ugly story, Erasmo said, returning his blade to the earth. Arnold, though, stared at the girl who did not seem such a girl anymore. He had misjudged her age, he thought, as so many misjudged his. Not twenty. Not sixteen. Not eighteen. Older than that. But he could not say how much older. Ten years. Twenty years. A hundred. She seemed an impossible age.

The crow, still brazenly perched on El Dorado’s hood, gave another squawk, but the cry sounded, this time, less like a bird and more like a woman. Erasmo tossed the shovel out of the hole and hoisted himself out, stalking menacingly toward the bird, which spread its wings and voiced its displeasure but did not take flight, not until Erasmo snatched up a stone from the forest floor and hurled it. The crow cried out and flew into the trees, and the stone, bouncing away, left behind a long, garish slash through the plate of gold coating.

He cursed, and swung himself back around, but it was the last thing he did. Ava had claimed the discarded shovel, and, with a cry of her own, swung it into his head. With a crunch, the corner of the blade lodged in his skull. His eyes crossed and his jaw fell slack, and he crashed first to his knees, then his face, the blood spurting from the fissure in his head like a geyser.

From the hip-deep hole, Arnold leaned on his shovel, watching placidly as the flow became a trickle, watching studiously as Ava tried to pry the shovel from the dead man’s skull, but without success; it was too firmly planted. Panting, she stumbled back from the body and turned to face Arnold. Such a curiosity, this one. She didn’t run. She didn’t speak. She only . . . waited. For what? For him? To see what he would do? So he asked her: Had it felt good, killing Erasmo? Had she liked it? She answered nothing. Only waited.

Very well, perhaps an invitation. He would ask her to join him, to be his replacement coadjutor, one thumb in the Rand McNally and the other tapping a wide steering wheel or the shaft of a shovel. She had grit, this one, intelligence and brashness, like a crow, waiting, watching, until—

Ava picked up a rock by her feet. When it struck him between the eyes, he was amazed. He had forgotten what it was to feel pain, raw and exquisite. His head fell backward, but before his own hot blood pooled into his eyes, he saw, in the trees above, what he had mistaken for shivering leaves, and which had been responsible for darkening the skies: crows. A thousand of them. Suddenly, they alighted from the branches, and the beating of their wings was like the roar of an oncoming train. Arnold fell back into the freshly dug grave as the black cloud descended on him, and he remembered, among his final thoughts, the black birds who had been there each time he had earned a new tally mark, witnessing the things he had done.

When the birds were gone, Ava buried them in the hole meant for Connie, deep enough for two. With the keys hanging from one finger, she gently folded Connie back into the trunk with a whispered an apology for all she had been through, and a compliment for her pretty shoes. Turquoise wasn’t Ava’s color, but she could appreciate it all the same. Then she hefted her pack and placed it in the passenger’s seat. It took two tries, but the Studebaker purred back to life with a turn on of the key. Easing between the trees, she returned to the road, driving back the way she had come.

Gasping on fumes, the car rolled into a gas station on the perimeter of a town. It was well past dark. While the tank filled, she pulled her phone from her pack, along with a portable charger, and sent a text. Then she drove through the night and into the next day and the next night until she came to city, and to a club, and behind the club, an alley. There, she laid Connie, where she knew she would be found. Later that night, maybe early in the morning, she would be found. No longer a missing person, no longer a question mark. She would be mourned, the way the dead ought to be mourned, and laid to rest in a suitable grave with a marker, bearing her name.

Sorrowful, but satisfied, Ava said her farewell, pulled the car to the street, and parked it two blocks away. She returned to the club, where the bass thrummed and the lights strobed blue and purple and red, and pushed her way through the mass of bodies until she found her friend, exactly where she said she’d be, jumping to the beat with her hands in the air. Ava tapped her friend’s bare shoulder, upon which she had tattooed a crow, and put her lips close to the woman’s ear: it was done, but there were others. Eight left to find. The woman stopped dancing and nodded. There was more work to do.

As they pushed their way through the crowd, toward the exit, they linked pinkies to keep together. How would they know where to go next, the woman wondered, and Ava said, wait and listen.

They drove. And as the sun began to crest in the East, they saw them: two birds, sharp silhouettes against pale orange clouds, flying north. The women leaned their heads forward to see them through the windshield. Moments later, they were joined by a third, a fourth, until the murder of crows, as synchronized as a school of fish, listed like a wave and turned north. At the next crossroads, Ava turned the wheel, following them, to discover what secrets they carried in their throats.

Holly Teresa Baker is a fiction writer from Indiana. She teaches writing at Purdue University.

You may like

Original Creations

Goodbye for Now, a Short Story by Jennifer Weigel

Published

3 weeks agoon

March 30, 2025What if ours weren’t the only reality? What if the past paths converged, if those moments that led to our current circumstances got tangled together with their alternates and we found ourselves caught up in the threads?

Marla returned home after the funeral and wake. She drew the key in the lock and opened the door slowly, the looming dread of coming back to an empty house finally sinking in. Everyone else had gone home with their loved ones. They had all said, “goodbye,” and moved along.

Her daughter Misty and son-in-law Joel had caught a flight to Springfield so he could be at work the next day for the big meeting. Her brother Darcy was on his way back to Montreal. Emmett and Ruth were at home next door, probably washing dishes from the big meal they had helped to provide afterward, seeing as their kitchen light was on. Marla remembered there being food but couldn’t recall what exactly as she hadn’t felt like eating. Sandwiches probably… she’d have to thank them later.

Marla had felt supported up until she turned the key in the lock after the services, but then the realization sank deep in her throat like acid reflux, hanging heavy on her heart – everyone else had other lives to return to except for her. She sighed and stepped through the threshold onto the outdated beige linoleum tile and the braided rag rug that stretched across it. She closed the door behind herself and sighed again. She wiped her shoes reflexively on the mat before just kicking them off to land in a haphazard heap in the entryway.

The still silence of the house enveloped her, its oppressive emptiness palpable – she could feel it on her skin, taste it on her tongue. It was bitter. She sighed and walked purposefully to the living room, the large rust-orange sofa waiting to greet her. She flopped into its empty embrace, dropping her purse at her side as she did so.

A familiar, husky voice greeted her from deeper within the large, empty house. “Where have you been?”

Marla looked up and glanced around. Her husband Frank was standing in the doorway to the kitchen, drying a bowl. Marla gasped, her hand shooting to her mouth. Her clutched appendage took on a life of its own, slowly relinquishing itself of her gaping jaw and extending a first finger to point at the specter.

“Frank?” she spoke hesitantly.

“Yeah,” the man replied, holding the now-dry bowl nestled in the faded blue-and-white-checkered kitchen towel in both hands. “Who else would you expect?”

“But you’re dead,” Marla spat, the words falling limply from her mouth of their own accord.

The 66-year old man looked around confusedly and turned to face Marla, his silver hair sparkling in the light from the kitchen, illuminated from behind like a halo. “What are you talking about? I’m just here washing up after lunch. You were gone so I made myself some soup. Where have you been?”

“No, I just got home from your funeral,” Marla spoke quietly. “You are dead. After the boating accident… You drowned. I went along to the hospital – they pronounced you dead on arrival.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Frank said. “What boating accident?”

“The sailboat… You were going to take me out,” Marla coughed, her brown eyes glossed over with tears.

“We don’t own a sailboat,” Frank said bluntly. “Sure, I’d thought about it – it seems like a cool retirement hobby – but it’s just too expensive. We’ve talked about this, we can’t afford it.”

Marla glanced out the bay window towards the driveway where the small sailboat sat on its trailer, its orange hull reminiscent of the Florida citrus industry, and also of the life jacket Frank should have been wearing when he’d been pulled under. Marla cringed and turned back toward the kitchen. She sighed and spoke again, “But the boat’s out front. The guys at the marina helped to bring it back… after you… drowned.”

Frank had retreated to the kitchen to put away the bowl. Marla followed. She stood in the doorway and studied the man intently. He was unmistakably her husband, there was no denying it even despite her having just witnessed his waxen lifeless body in the coffin at the wake before the burial, though this Frank was a slight bit more overweight than she remembered.

“Well, that’s not possible. Because I’m still here,” Frank grumbled. He turned to face her, his blue eyes edged with worry. “There now, it was probably just a dream. You knew I wanted a boat and your anxiety just formulated the worst-case scenario…”

“See for yourself,” Marla said, her voice lilting with every syllable.

Frank strode into the living room and stared out the bay window. The driveway was vacant save for some bits of Spanish moss strewn over the concrete from the neighboring live oak tree. He turned towards his wife.

“But there’s no boat,” he sighed. “You must have had a bad dream. Did you fall asleep in the car in the garage again?” Concern was written all over his face, deepening every crease and wrinkle. “Is that where you were? The garage?”

Marla glanced again at the boat, plain as day, and turned to face Frank. Her voice grew stubborn. “It’s right here. How can you miss it?” she said, pointing at the orange behemoth.

“Honey, there’s nothing there,” Frank exclaimed, exasperation creeping into his voice.

Marla huffed and strode to the entryway, gathering her shoes from where they waited in their haphazard heap alongside the braided rag run on the worn linoleum floor. She marched out the door as Frank took vigil in its open frame, still staring at her. She stomped out to the boat and slapped her hand on the fiberglass surface with a resounding smack. The boat was warm to the touch, having baked in the Florida sun. She turned back towards the front door.

“See!” she bellowed.

The door stood open, empty. No one was there, watching. Marla sighed again and walked back inside. The vacant house once again enveloped her in its oppressive emptiness. Frank was nowhere to be found.

So I guess it’s goodbye for now. Feel free to check out more of Jennifer Weigel’s work here on Haunted MTL or here on her website.

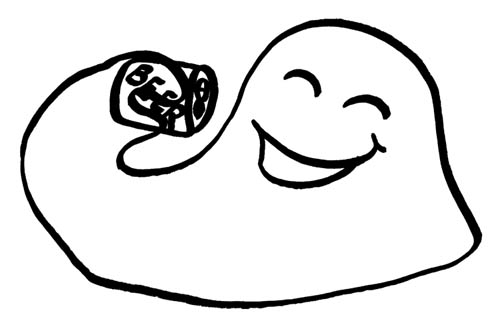

Today on Nightmarish Nature we’re gonna revisit The Blob and jiggle our way to terror. Why? ‘Cause we’re just jellies – looking at those gelatinous denizens of the deep, as well as some snot-like land-bound monstrosities, and wishing we could ooze on down for some snoozy booze schmoozing action. Or something.

Honestly, I don’t know what exactly it is that jellyfish and slime molds do but whatever it is they do it well, which is why they’re still around despite being among the more ancient organism templates still in common use.

Jellyfish are on the rise.

Yeah, yeah, some species like moon jellies will hang out in huge blooms near the surface feeding, but that’s not what I meant. Jellyfish populations are up. They’re honing in on the open over-fished ocean and making themselves at home. Again.

And, although this makes the sea turtles happy since jellies are a favorite food staple of theirs, not much else is excited about the development. Except for those fish that like to hide out inside of their bells, assuming they don’t accidentally get eaten hanging out in there. But that’s a risk you gotta take when you’re trying to escape predation by surrounding yourself in a bubble of danger that itself wants to eat you. Be eaten or be eaten. Oh, wait…

So what makes jellies so scary?

Jellyfish pack some mighty venom. Despite obvious differences in mobility, they are related to anemones and corals. But not the Man o’ War which looks similar but is actually a community of microorganisms that function together as a whole, not one creature. Not that it matters when you’re on the wrong end of a nematocyst, really. Because regardless what it’s attached to, that stings.

Box jellies are among the most venomous creatures in the world and can move of their own accord rather than just drifting about like many smaller jellyfish do. And even if they aren’t deadly, the venom from many jellyfish species will cause blisters and lesions that can take a long time to heal. So even if they do resemble free-floating plastic grocery bags, you’d do best to steer clear. Because those are some dangerous curves.

But what does this have to do with slime molds?

Absolutely nothing. I honestly don’t know enough about jellyfish or slime molds to devote the whole of a Nightmarish Nature segment to either, so they had to share. Essentially, this bit is what happened when I decided to toast a bagel before coming up with something to write about and spent a tad too much time in contemplation of my breakfast. I guess we’re lucky I didn’t have any cream cheese or clotted cream…

Oh, and also thinking about gelatinous cubes and oozes in the role-playing game sense – because those sort of seem like a weird hybrid between jellies and slime molds, as does The Blob. Any of those amoeba influenced creatures are horrific by their very nature – they don’t even need to be souped up, just ask anyone who’s had dysentery.

And one of the most interesting thing about slime molds is that they can take the shortest path to food even when confronted with very complex barriers. They are maze masterminds and would give the Minotaur more than a run for his money, especially if he had or was food. They have even proven capable of determining the most efficient paths for water lines or railways in metropolitan regions, which is kind of crazy when you really think about it. Check it out in Scientific American here. So, if we assume that this is essentially the model upon which The Blob was built, then it’s kind of a miracle anything got away. And slime molds are coming under closer scrutiny and study as alternative means of creating computer components are being explored.

Jellies are the Wave of the Future.

We are learning that there may be a myriad of uses for jellyfish from foodstuffs to cosmetic products as we rethink how we interact with them. They are even proving useful in cleaning up plastic pollution. I don’t know how I feel about the foodstuff angle for all that they’ve been a part of various recipes for a long time. From what I’ve seen of the jellyfish cookbook recipes, they just don’t look that appealing. But then again I hate boba with a passion, so I’m probably not the best candidate to consider the possibility.

So it seems that jellies are kind of the wave of the future as we find that they can help solve our problems. That’s pretty impressive for some brainless millions of years old critter condiments. Past – present – perpetuity! Who knows what else we’d have found if evolution hadn’t cleaned out the fridge every so often?

Feel free to check out more Nightmarish Nature here.

Original Series

Lucky Lucky Wolfwere Saga Part 4 from Jennifer Weigel

Published

1 month agoon

March 17, 2025Continuing our junkyard dawg werewolf story from the previous St. Patrick’s Days… though technically he’s more of a wolfwere but wolfwhatever. Anyway, here are Part 1 from 2022, Part 2 from 2023 and Part 3 from 2024 if you want to catch up.

Yeah I don’t know how you managed to find me after all this time. We haven’t been the easiest to track down, Monty and I, and we like it that way. Though actually, you’ve managed to find me every St. Patrick’s Day since 2022 despite me being someplace else every single time. It’s a little disconcerting, like I’m starting to wonder if I was microchipped way back in the day in 2021 when I was out lollygagging around and blacked out behind that taco hut…

Anyway as I’d mentioned before, that Scratchers was a winner. And I’d already moved in with Monty come last St. Patrick’s Day. Hell, he’d already begun the process of cashing in the Scratchers, and what a process that was. It made my head spin, like too many squirrels chirping at you from three different trees at once. We did get the money eventually though.

Since I saw you last, we were kicked out of Monty’s crap apartment and had gone to live with his parents while we sorted things out. Thank goodness that was short-lived; his mother is a nosy one for sure, and Monty didn’t want to let on he was sitting on a gold mine as he knew they’d want a cut even though they had it made already. She did make a mean brisket though, and it sure beat living with Sal. Just sayin.

Anyway, we finally got a better beater car and headed west. I was livin’ the dream. We were seeing the country, driving out along old Route 66, for the most part. At least until our car broke down just outside of Roswell near the mountains and we decided to just shack it up there. (Boy, Monty sure can pick ‘em. It’s like he has radar for bad cars. Calling them lemons would be generous. At least it’s not high maintenance women who won’t toss you table scraps or let you up on the sofa.)

We found ourselves the perfect little cabin in the woods. And it turns out we were in the heart of Bigfoot Country, depending on who you ask. I wouldn’t know, I’ve never seen one. But it seems that Monty was all into all of those supernatural things: aliens, Bigfoot, even werewolves. And finding out his instincts on me were legit only added fuel to that fire. So now he sees himself as some sort of paranormal investigator.

Whatever. I keep telling him this werewolf gig isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be, and it doesn’t work like in the movies. I wasn’t bitten, and I generally don’t bite unless provoked. He says technically I’m a wolfwere, to which I just reply “Where?” and smile. Whatever. It’s the little things I guess. I just wish everything didn’t come out as a bark most of the time, though Monty’s gotten pretty good at interpreting… As long as he doesn’t get the government involved, and considering his take on the government himself that would seem to be a long stretch. We both prefer the down low.

So here we are, still livin’ the dream. There aren’t all that many rabbits out here but it’s quiet and the locals don’t seem to notice me all that much. And Monty can run around and make like he’s gonna have some kind of sighting of Bigfoot or aliens or the like. As long as the pantry’s stocked it’s no hair off my back. Sure, there are scads of tourists, but they can be fun to mess around with, especially at that time of the month if I happen to catch them out and about.

Speaking of tourists, I even ran into that misspent youth from way back in 2021 at the convenience store; I spotted him at the Quickie Mart along the highway here. I guess he and his girlfriend were apparently on walkabout (or car-about) perhaps making their way to California or something. He even bought me another cookie. Small world. But we all knew that already…

If you enjoyed this werewolf wolfwere wolfwhatever saga, feel free to check out more of Jennifer Weigel’s work here on Haunted MTL or here on her website.