Win the Game, or Here You’ll Stay – Reviewing “Doctor Who: the Celestial Toymaker” New Animation

It’s been an interesting journey for the story from 1966 – from lost myth, to scandalous disappointment. Will this new animated version allow a reappraisal?

More Videos

Published

9 months agoon

By

J M

“The Celestial Toymaker” as a serial has had quite a mixed history in fandom circles. It was first broadcast in April 1966 as part of the third season of Doctor Who, and like most of the stories of that season, the original episodes were eventually wiped from the BBC. While Episode 4 – “The Final Game” was found in Australia in 1986, there was twenty years it existed as a fan memory, with information shared in fanzines based on these memories celebrating the creativity and fantasy elements of the story. There was even a plan in 1985 to bring back the character for the cancelled original season 23 story “The Nightmare Fair” where he would use video games and theme park threats to menace Colin Baker’s sixth Doctor.

After the final episode was found in 1986, there slowly was a reappraisal of the story. While early Doctor Who special effects and staging were never seen as a strength, the original story’s budget was basically a shoestring. A retrospective by Doctor Who Magazine in the early 2000’s called it boring. In 2011, Elizabeth Sandifer in their Eruditorum Press blog, highlighted the racist aspects of the story, such as the use of a racial slur spoken by a minor character in episode two (thankfully concealed from all media releases), and the character of the Toymaker himself as a Fu Manchu style Asian stereotype. The term “Celestial” itself, while often taken to mean “From the sky” is also an old time slur for the Chinese. Russell T Davies in the lead up to the Toymaker’s return in “The Giggle” acknowledged he was aware of this in interviews, and had the character play with accents using race as an attack against others.

So like with many of the very lost stories of the sixties, it’s been an interesting journey for how “The Celestial Toymaker” has been seen. And the last time I sat down to watch the surviving episode, my partner lasted five minutes into watching characters throw dice on the floor before leaving the room and not returning. And she had a point.

But this review isn’t about the original 1966 production. In light of the Toymaker’s triumphant return in 2023’s “The Giggle” a newly animated version of the original 1966 story has been released to allow fans to have better access to this returning villain.

Story Outline

As was standard with the series in 1966, the story begins at the conclusion of the previous story “The Ark” with the Doctor (William Hartnell) suddenly becoming invisible and warning his companions Steven (Peter Purves) and Dodo (Jackie Lane) they were in grave danger. Exiting the TARDIS, the Doctor finds his form has returned, and after being tempted by windows displaying their memories, they are confronted by the Toymaker (Michael Gough). The Toymaker says in order to leave they must play his games, the Doctor being transported away to play the Trilogic Game (Better known as Towers of Hanoi), with Steven and Dodo completing several other games in order to find the TARDIS.

Each of these games is a variation of popular games of the time, such as Blind Man’s Bluff, musical chairs, and hunt the thimble, but with the threat of failure resulting in Steven and Dodo becoming eternal play things of the Toymaker. Meanwhile the Doctor is unable to assist his companions, as the Toymaker demonstrates his power by removing his speech, and reducing him to one hand, operating the game.

While the concept is interesting, and demonstrative of the wide variety of story styles in a series that didn’t have a set format a yet, in practice, watching a bunch of character actors play simple games is a slow and dull spectacle to watch. This isn’t helped by the last episode featuring the game “TARDIS hopscotch” where characters roll dice, and jump from base to base.

Production Turmoil

Behind the scenes, this is an era of Doctor Who of inner turmoil. William Hartnell’s health was declining, with his as yet undiagnosed condition of arteriosclerosis resulting in memory lapses and irritability. Previous production teams, who had known how to work well with Hartnell, had been replaced, alongside much of the cast that he had been close with. As a result, there was a new production team which did not have a good working relationship with Hartnell, and Hartnell often taking extended breaks within stories. Towards this part of Season 3, almost every second story had the Doctor somewhat incapacitated or absent, and in “The Celestial Toymaker” the Toymaker reduces the Doctor to just a hand for most of the first three episodes.

As regeneration would not be created as a plot device until the following season, there had been a plan to have the Toymaker change the Doctor’s appearance when he becomes visible again, and have the new recast Doctor become the main character following. While this plan was vetoed (And the producer who had the plan subsequently left the production of this story), some elements may have lead to the idea of what we now know as regeneration.

There had also been issues raised about the new companion of Dodo Chaplet, introduced five episodes previously. Originally developed as a down to earth modern girl with a Cockney accent, her accent was changed to BBC standard English from this story until her departure at the final story of the season. This was evidence of a different view between the production team wanting to move the series to reflect a youth audience, and the policies of the BBC of the day to only allow certain accents. However, by the end of the season, with the introduction of cockney sailor Ben Jackson as a companion, diversity of accents was eventually accepted.

Missing Stories

In the 1960’s there was not a view that television need to be stored. Home video was two decades away, repeats were rare, and tape was expensive and a fire hazard to store. As a result, many shows had episode, or entire seasons, wiped by the production teams of the time. Doctor Who is one of the most known series effected by this decision, but definitely not the only one, with series like “The Avengers” “Hancock’s Half Hour” and many more having most of their seasons almost entirely lost.

Fans of the time, while unable to record video, were able to record audio tapes of each episode, and this has meant that “Missing stories” have been able to be enjoyed by fans today either as narrated audio, or combining these audio tracts with existing pictures of the story.

Since 2006, the BBC had looked into animation studios to created animated reconstructions of these missing stories. Originally just attempting to recreate stories as they would have been shown in the 1960’s, since 2019 animation studios have increasingly tried to make a new version of the story, based on the ideas in the script, rather than the limits of what was possible in the budget of the day. The result of that is stories, such as 1967’s “The Macra Terror” featuring far more expressive and mobile monsters than were possible originally.

While the decision to change the stories somewhat substantially was a controversial one, it’s a decision I’ve very much approved of. Rather than make an animated reconstruction which will never match with what the original broadcast episodes would have looked like, instead a new story is created. In cases where these stories and their plots have been known for decades, there is an excitement in finding a new way to make them, and seeing what the animators have been inspired to make from the script.

The New Updated Animated Version – Pros and Cons

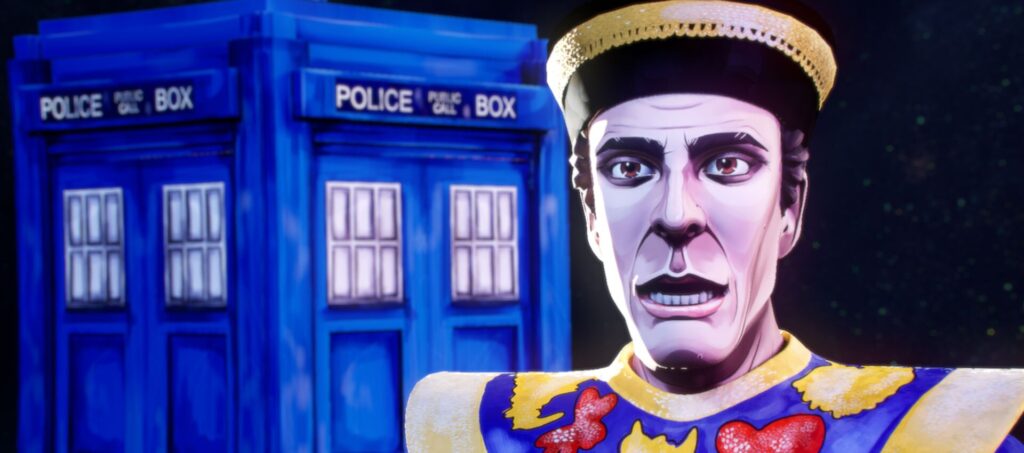

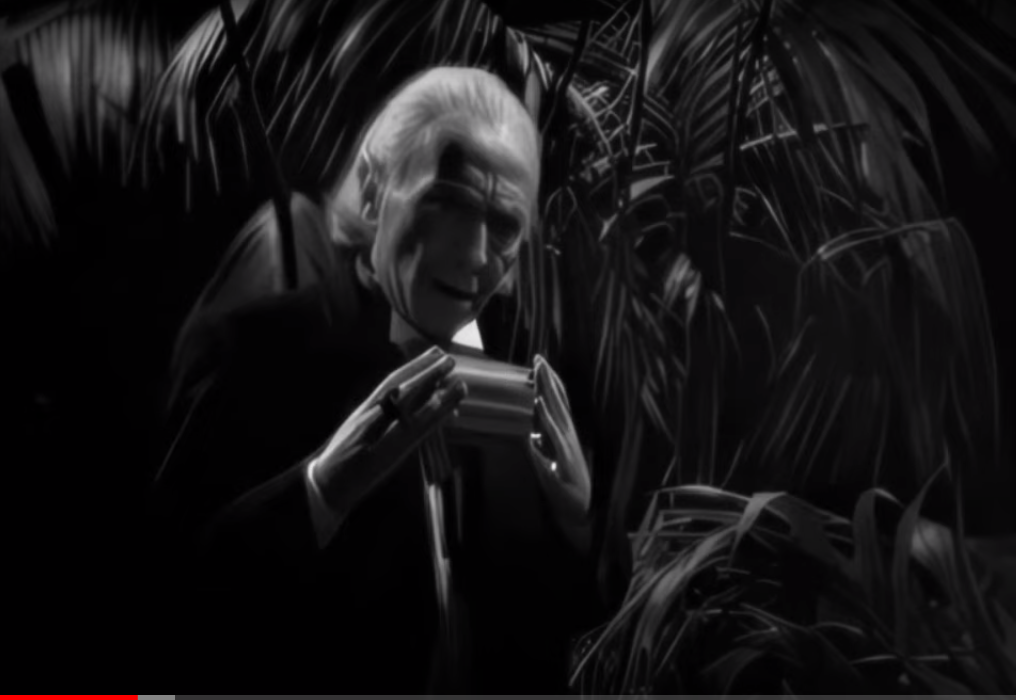

“The Celestial Toymaker” is the newest of these animations, and with a style that is quite distinct from most animations that have occurred before. Whereas most of the last productions were producing simple flash style 2D animation, the style used for Celestial Toymaker seems more three dimensional, with textures and crevices more noticeable on the faces of the cast.

This new style of animation has its drawbacks, and at first glance in the trailer earlier this year, the visualizations of the main cast was off putting to me. The way the mouth of most characters move seems not to match the sounds, with often just the lower lip moving to give the impression of speech.

Each human character, no matter their age, seemed to have old, tired eyes. While I reminded myself that no Doctor Who animated feature has been amazing when it came to showing human expression and emotion, the portrayal of the human cast in “The Celestial Toymaker” is a good example of the uncanny valley – they have ceased looking like a cartoon, but instead look like people with something wrong.

However, the animation team for this project have also used “the uncanny valley” for their benefit. Because while out of context, the animated versions of the human cast look wrong, for this particular story, in this particular context, looking uncanny makes sense. The Celestial Toyroom is an uncanny place – it’s meant to be outside of time and space, a world where the only rules are those determined by a God like creature obsessed with games. And this new animated version really reflects it.

Starting with the non-regular cast, not having to use a physical human being for a cast has freed the team to create a range of characters that would not be possible to feature easily in Doctor Who, even today. A comical chef character in episode three is now a life size knitted doll, and the movements which look awkward on an animated human, look sensible on a doll filled with stuffing. Dancing dolls which were originally just human dancers are now wooden dolls, with the wood grain visible on each face. The Toymaker himself seems to shrink and grow to giant sizes on a whim. The playing card characters in episode two, previously just actors dressed to look like the Kings and Queens appearing on a playing card deck, are now cards with stick arms and legs.

The settings also show a world where physics do not make sense. Steven completing an obstacle course can suddenly be walking on the ceiling. Transition between games occurs by crossing toy blocks seemingly hovering above a mist of nothingness. The game of jumping from shallow platforms across the floor, is now jumping through the air, with electrical sparks threatening the cast below.

The best example of how these themes combine is in episode three. As Dodo and Steven enter the dancing floor, there is a musical interlude where the dancing dolls as scripted finish their routine. It’s quite a long musical number, and nothing happens in it. The animated version instead has Dodo and Steven drifting through a void, falling through the Toymaker’s mouth, onto a form of the TARDIS, only to be reformed at the end of the musical montage. The creativity shown in this scene makes it, in my mind, the greatest piece of animated Doctor Who ever made.

While most animated reconstructions have allowed fans to appreciate and enjoy stories which are now lost, with “The Celestial Toymaker” we actually have a reconstruction which enhances on the original. The settings are exciting, the characters visually interesting, and the threat is apparent throughout the animation where it was not before. While no further animations are announced, if this is the new bench mark on what could be aimed for, I hope we see more of this in the future.

In particular, get this team of recreate “The Space Pirates” from 1969, and let them go to town to recreate a space opera without relying on 1969’s model effects.

(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)

A Writer based in Melbourne Victoria, focusing on Doctor Who, in particular areas of the Extended Universe and little known stories deserving of love.

You may like

-

Identical: Yes. The Same: No – Exploring the World of AI Reconstructions in Doctor Who

-

The Hotel: We’ll All Be There Soon.

-

“How to Split an Atom,” a Scientific Return to Evil

-

Victorian Psycho: She’s Paranoid, Violent and Utterly Charming

-

Starve Acre: The womb of nature

-

“The Demon of the End” Trumpeting New Evil

Doctor Who

Identical: Yes. The Same: No – Exploring the World of AI Reconstructions in Doctor Who

Published

4 weeks agoon

March 19, 2025By

J M

The second half of 2024 was a bit of slow for Doctor Who news. Ncuti Gatwa’s first season finished in June, and the Christmas special was months away. Comics and audio plays continued, and a Blu-Ray set of Season 25 was released – but that was all.

However, what was new and exciting was a spate of unofficial recreations of missing Doctor Who stories from the sixties. Re-animations of missing stories have occurred previously, both officially by the BBC and unofficially by fans. However, animation production time means it’s rare to have more than a few episodes a year. However within the space of six months, forty-four recreated episodes were released, with the promise of more to come.

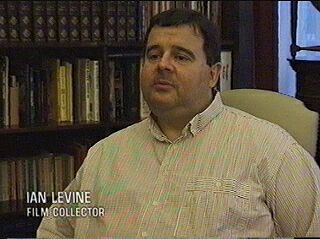

The reason how so many stories have been released so quickly is artificial intelligence (AI). These reconstructions are Generative AI, funded by professional songwriter, film producer, and fan, Ian Levine. This decision to make Doctor Who AI Reconstructions, to put it mildly, has been controversial online.

But is it worth it, in order to having otherwise missing stories returned to us? I’ve examined many of these Doctor Who AI reconstructions, and the discourse around them, to find out.

In Brief – Missing Episodes

A decent proportion of Doctor Who’s earliest years shockingly does not exist anymore. Doctor Who is one of the BBC’s biggest revenue raisers, and most famous show around the world. However it was not always the case.

When Doctor Who first began in 1963, the idea of keeping media was not really considered. Home video did not exist, and would not exist for two decades. Repeats were rare, due to the costs at the time to store old material and pay people involved in them. Also, old film presented a fire hazard. So it was often disposed of.

Despite this, Doctor Who is fairly lucky compared to other series. Firstly, fans at the time recorded the audio of each story. This means even the first ever Christmas Special – “A Feast of Stephen,” never broadcast internationally or repeated, still exists as an audio.

Doctor Who is also lucky because of only six seasons are not complete. In addition, of those six seasons, only half are missing only episodes from one or two stories. This allows us to get a feel for the early years of Doctor Who in a way fans of other series, like “Quatermass” and “The Avengers” aren’t able to. And part of the reason most of these early seasons survive is due to Ian Levine.

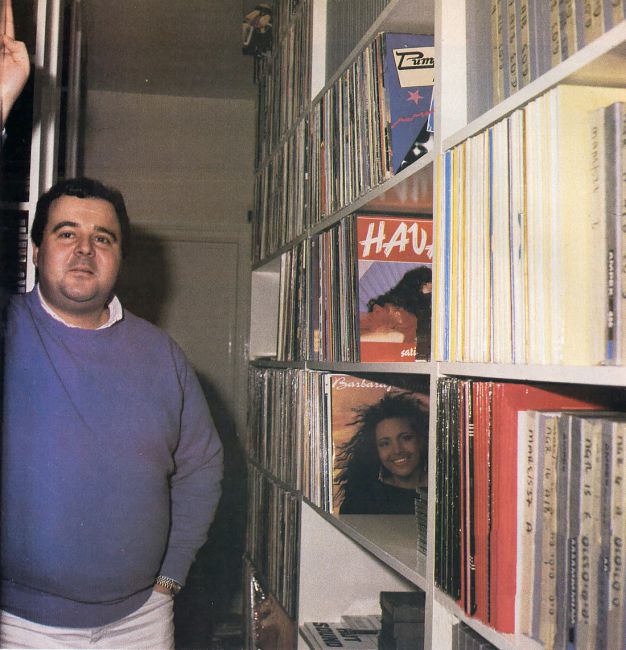

Who is Ian Levine?

Ian Levine professionally is a songwriter and DJ. He has written and produced records connected to such bands as Take That, Pet Shop Boys, Bananarama and Bucks Fizz. His total sales exceed 40 million records.

He is also well known as a prominent Doctor Who fan. There are many prominent Doctor Who fans. The series from 2004 onwards has been largely made by prominent Doctor Who fans of the 70’s and 80’s. Many of these fans contribute to Doctor Who in official ways. For instance, many older fans have written books, or audio plays. All three showrunners for the modern series would be considered prominent fans from the nineties. For Ian Levine, his main contribution is seeking to find and restore missing episodes of Doctor Who.

This work started in 1978 where Levine reportedly requested the permanent halting of old episodes of Doctor Who. At the time the idea of home video was being considered, leading to more reasons to keep old film. Levine also claimed to have rescued the first ever Dalek story from being sent into a furnace. Following this, he began purchasing private copies of the remaining stories, and attempting to return them to the BBC.

He also connected with the Doctor Who Production Team of the eighties in other ways. This included composing the theme tune for the spin-off series “K-9 and Company”, and the protest/charity album “Doctor In Distress.” His was also consulted about continuity during seasons eighteen to twenty-two.

However, he also gained a notorious reputation as obsessive in an unappealing way. During the 1985 Doctor Who hiatus, Levine was encouraged by Producer Jon Nathan-Turner to use protest the decision. Levine argued against the decision on television, and smashed his television with a hammer, and inviting newspapers to photograph it.

So he is fan who has both done great things, but also sought notoriety and negative attention.

More recently, Levene has worked with animating missing or incomplete episodes. This started in 2010 with “Mission to the Unknown.” This was not allowed to be shared or sold due to it being made without BBC authorization. In 2013, Ian hired an animated reconstruction of the unfinished story “Shada.” This version used pre-existing footage and new audio to create a finished product he hoped could be licensed. However, the BBC chose not to. Instead they made their own animated version that was released four years later.

- Join the Doctor (Tom Baker), Romana (Lalla Ward), and K-9 (voiced by David Brierley) as a visit to a Time Lord living incognito on Earth leads to a desperate race to a distant prison planet

- A BBC strike halted filming of this never-broadcast Baker six-episode serial written by “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” author Douglas Adams

- Christopher Neame, Victoria Burgoyne co-star

Last update on 2025-03-16 / Affiliate links / Images from Amazon Product Advertising API

Subsequently, Levine made comments regarding Jodie Whittaker as the first female Doctor which were deemed by many to be sexist. Levine responded by publicly quitting the fandom, though later created his own private Doctor Who Facebook group.

This group has now become the location where his AI recreations he has funded and received donations for are shared.

The Doctor Who AI Reconstructions – How to Access

The Facebook Page: “Ian Levine’s Facebook Group” requires an agreement to two questions to join. Firstly, you must agree to respect the right to criticize Jodie Whittaker. Secondly, you must recognise this is Ian Levine’s group for sharing his opinions on Doctor Who. Agree to all this, and you’re allowed in.

Inside the group, Levine has shared around twenty videos. This includesall of “The Dalek Masterplan,” “The Massacre,” and “The Savages.” However for the remainder, you must make a donation of fifty pounds, to become a contributor to the series.

Once your donation is confirmed, you are authorized to join the separate contributors group, for contributors only. This is where all the current videos being made are released.

Except…. None of these videos are unavailable privately. Ian Levine has placed them all on Youtube. They are unlisted, so they cannot turn up in either a Google or YouTube search. However, if you have a direct link or URL to them, they are accessible to everyone. Unlike other systems like Patreon which restrict content to only certain subscribers, nothing stops these links being shared elsewhere.

And of course, these links are shared. In response, Levine has issued threats and warnings against other Facebook groups and leakers trying to destroy his vision. In his group, people support him and join in denouncing those who criticize his work or mock it. People outside the group in response denounce Ian Levine and his supporters.

One thing I hate about internet culture is the push for tribalism. This is the idea we are joined in a selective tribe and must fight the rivals to connect. Over time the views become more strict in supporting your own tribe, and rejecting the opposition, and the middle ground is lost.

In the case of Ian Levine’s group, this is best shown by the view of alternative animations of missing Doctor Who stories. All of these are seen as not as good as Levine’s AI reconstructions. Levine’s reconstructions are seen as the only correct way Doctor Who is meant to be.

Initially Ian Levine’s AI project aimed to complete the ten missing stories not completed by the BBC. The initial project recognised the slow time it took to animate missing stories, and focused on stories that were difficult and costly to animate with people. Very soon after, however, Levine denounced many of the prior animations as “Silly Scooby Doo Cartoons.” The project was quickly extended to include stories previously animated by the BBC. Levine’s argument appears to be Levine’s objections to story changes animation had included. These included adding a surprise image of the Master in “Fury from the Deep”, prior to his debut appearance. Given Levine’s history of making things for the BBC, with the hope the BBC would license them, there have been rumours Levine initially was hoping the BBC would license some of his AI recreations, which has not come to pass.

Levine presents his animations as the most authentic way to view the missing episodes. Therefore appreciation of official animated reconstructions are not allowed. A poster saying they enjoyed the animated version of “The Celestial Toymaker,” was informed by Levine tht anyone who enjoyed the animation was unwelcome. Common responses of new animations being announced are people accusing the BBC of ruining another story. When Levine had a fault pointed out in one of his stories by Frazer Hines, who played the second Doctor’s companion, Jamie, Levine’s first response was to accept that the animation had limitations, but insisted it was still better than any animation the BBC has made. Most of all, posters all reinforce the message that AI reconstructions are the true version of the lost stories and the BBC are fools for not paying for them.

- The Celestial Toymaker sees the Doctor and his companions separated when they come up against the Toymaker

- While the Doctor plays the Trilogic Game, Steven and Dodo are forced to play their own seemingly childish, but ultimately dangerous games, with the aim of being reunited and getting back to the TARDIS

- Who will be the first to make a false move in this battle of wits, and will the TARDIS ever escape the Toymaker’s snare Fans of Doctor Who have long lamented the loss of the original 1966 master recordings of all except one of The Celestial Toymaker

Last update on 2025-03-16 / Affiliate links / Images from Amazon Product Advertising API

In response to this, or provoking this, depending on your point of you, external Facebook groups and YouTube channels are highly critical of the AI reconstructions. Some videos see them as threats, preventing the BBC from every investing in animation involving real people. Some hav dismissed the project as a scam.

So with such strong opinions on both sides, it’s time to actually watch them.

The AI Reconstructions

My first response on watching is they’re not that bad, but they’re not that good. Animation varies wildly in quality from story to story, making it hard to tell an overall trend towards or away from quality. However there are some good examples of how to recreate a story. “The Massacre” and “The Dalek Masterplan” for instance are incredible to watch. “The Savages” on the other hand is laughingly bad.

I chose to mostly focus on the stories not yet officially animated, so as to judge these stories by their own merit rather than compare to other animated versions of the same stories. However, it’s interesting the similarities that occur between the official animations and AI reconstructions. Non human characters (Particularly Daleks) look and move great, but people largely do not.

Animating People

Across most forms of Missing episode recovery, whether AI or human drawn, the difficulty is always animating people to show emotions and movement. Many of the official BBC animations often leave characters looking like stick figures bobbing up and down.

However one of the key things the official reconstructions provide is consistency. A human being develops a pre-existing model for characters, and because of this, these characters stay consistent over time.

AI on the other hand appears to forget things, or lose focus unless properly guided. People’s faces can change dramatically from shot to shot to the point, as in “The Savages” characters can be unrecognizable. This means, unlike with official animations, I often had to follow a story summary to figure out what was going on.

AI also forgets smaller things that make people seem human. In “The Highlanders” for instance the Doctor’s companion Polly does not blink for most of episode one, despite being in shot. This is a small detail, but throws the story into the uncanny valley – characters involve look like people but they feel wrong based on how they act.

Movement is a struggle for all reconstructions because human movement is difficult to animate. Once again, “The Massacre” demonstrates small examples of movement than seem fluid, particularly in the first episode. “The Savages” on the other hand has main characters seemingly to perform scissor jump spread legged when the script call on them to walk.

How the animation occurs

Having watched many of these animations, some of means AI generated these reconstructions became clearer. A lot of these animations, especially some of the later ones, do not actually generate much new material, instead using existing material in different ways. The First Doctor saying goodbye to Susan in the TARDIS, from Episode 6 of the Dalek Invasion of Earth, for instance is frequently re-used. This scene is redubbed multiple times in the reconstructions, when a missing story needs a scene of William Hartnell standing alone in the TARDIS.

Another method is using the telesnaps, and slightly animating the mouth and face. This creates a sense of fluidity and movement, but a very limited one. This is particularly noticeable in the Space Pirates. The resconstructions rely on switching between static photos of one cast member with mouths moving. On the one hand, this is no worse than the telesnaps, but the telesnaps were aware of their limitations, so often would use narration or subtitles to fill the gaps. However these reconstructions are presented as the most life like renditions of the missing episodes. As the original story did not have subtitles or narration, therefore, they are not allowed. As a result the story is incomprehensible.

Benefit – it exists

But despite the complaints, there is a significant benefit in these reconstructions. And that’s the fact that they exist.

Currently nine missing stories have not been officially animated by the BBC. I would love for all missing stories to be animated. However, the reality is most of the stories remaining might be too costly to animate.

Of the nine stories, six are pure historicals – stories with no science fiction elements apart from the TARDIS and its crew. These stories tended to have a larger number of human characters than stories with monsters, and a human being with their range of emotions is harder to animate than a Dalek.

Historicals also tend to have more detailed and complex scene change. A story in the future can replicate cold, grey corridors throughout a space colony. Historicals however must recreate significant locations in the world at particular times in history. Having to recreate 15th century France, for instance, is made up of multiple distinct locations. This makes historical stories more time consuming and therefore costly to animate. Therefore, despite stories being reanimated for almost twenty years now, the total number of historical episodes animated have been two – both missing episodes of the Reign of Terror.

For the remaining three stories, the limited human cast and isolated space station locations makes Wheel in Space relatively simple to animate. The Space Pirates, may also be animated as the story focusing mostly on space ships should make some aspects of the design easier to manage.

That just leaves The Dalek Masterplan¸ a massive twelve episode story, with a one episode prequel, where the Daleks chase the Doctor throughout time and space. The cast is huge, and while it is not a historical, the story would require animated sets of ancient Egypt during the building of the pyramids. None of this would be easy to do on the current BBC animation budget.

Therefore, it appears of the remaining nine missing stories, only two are highly likely to be animated.

And this is where AI can play a role. As AI does not rely much people, it means the costs to recreate a story like the Dalek Masterplan is significantly easier and cheaper than hiring a production studio to make it. While the end result is not as good as a professionally animated episode, for stories where hiring professional animations is not feasible, this is one way for people to observe a version of a story we otherwise cannot access.

Ultimately the frustrating thing about these reconstructions is they’re not allowed to be what they are. If they were simply an attempt to make otherwise lost stories more accessible, without any pretention or idea of superiority they would be fine. There are no shortages of fan made reconstructions, which vary in quality, but are all warmly received because they don’t pretend to be more than fan made animations. They are no better or worse than any other reconstructions.

If Levine’s reconstructions were presented with the same humbleness, the response would be more positive. If Leveine would present it as a project, and be accepting of others not needing to accpet them, there would be less retaliation online. But they aren’t presented as a fun way to view a loss episode. The reconstructions are presented as the only correct way to view the stories, superior than any other effort. In fact, he considers the stories no longer lost due to his AI reconstructions.

But by doing so, he puts the reconstructions on a pedestal of perfection. But they aren’t perfect, not by a long shot. By Leveine presenting these as perfect, he ultimately encourages people to notice how they are lacking by comparing to perfection. In comparison, more humble attempts of reconstruction, by presenting themselves as not the best, encourage people to notice what they do right.

So, try to enjoy the reconstructions for what they are. Some are surprisingly good – especially The Dalek Masterplan and The Massacre, and it’s a chance to see stories animated that you may not get to see animated elsewhere. But try to filter out all the rhetoric about how amazing and perfect they should be, and just enjoy them as they are.

(2 / 5)

(2 / 5)

Related posts:

Doctor Who

The Most Dangerous President in Doctor Who History Isn’t Who You’d Think

Published

5 months agoon

November 5, 2024By

J M

Happy Election Day for all those who choose to celebrate. I was originally planning to run down the list of the most extreme American Presidential portrayals featured in Doctor Who. However I quickly realized this would not be possible. This is because most times when the American President appears in Doctor Who, the series treats them nicely.

Sure, the Eleventh Doctor said Richard Nixon was “Not one of the good ones” in “The Impossible Astronaut,” but that was the limit of the criticism. The very real Harry S Truman, and the very fictional Tom Dering, were manipulated into almost starting a nuclear war. However the Doctor in both cases sees them as victims of the manipulations of beings arriving from outside of Earth. Since Donald Trump’s election in 2016, most references to him in Doctor Who media have been jokes on the basis of his appearance.

Compare this to how the series treats the role of Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. We’ve had Prime Ministers who wanted to start a nuclear war, for no clear reason, in Roger ap Gwilliam. One Prime Minister was secretly a Sea Devil in the comic strip Clara Oswald and the School of Death. Prime Minister Greyhaven acted as a Quisling to the invading Ice Warriors The Dying Days. And of course, the Master as Harold Saxon became Prime Minister of England, and proceeded to wipe out ten percent of humanity.

So unlike the leaders of the UK, Doctor Who tends to be slightly more respectful when it comes to Presidents of the United States. So there’s not a lot of terrible, weird, or dangerous Presidents to discuss.

Except for one. And to discuss this one, we need to talk about the world of Faction Paradox.

Faction Paradox – Origins

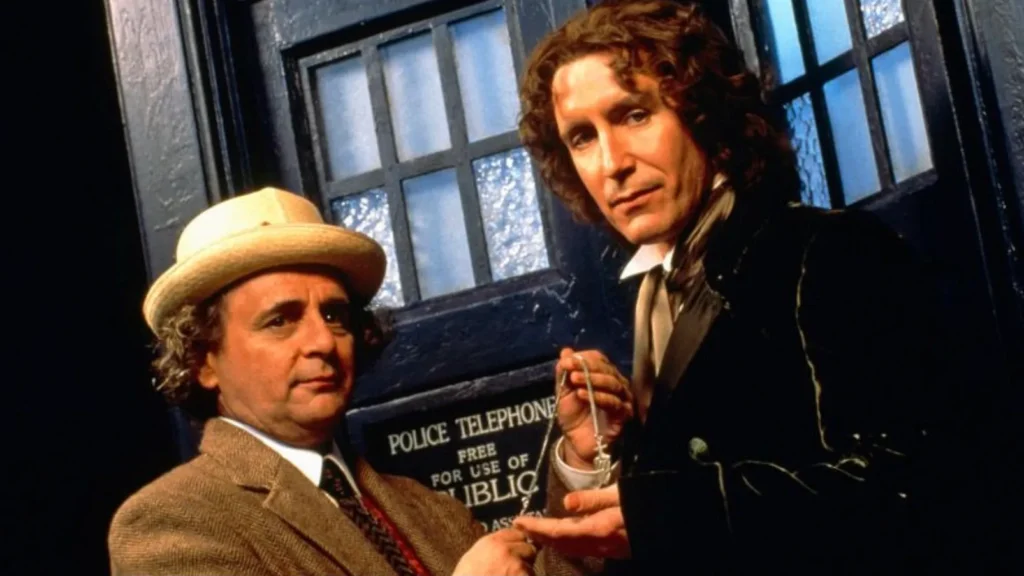

The year is 1997. The TV Movie from the previous year introduced the world to the Eighth Doctor as portrayed by Paul McGann. However, a new series, or sequel following on from that did not appear. Instead, the ongoing story of Doctor Who continued in the world of BBC Eighth Doctor Adventures.

This series developed in response to the Movie, allowing people to see what the Eighth Doctor did next. Initially the series focused on safer and familiar Doctor Who story tropes. Previous series had tried to push the boundaries and concepts for a more mature audience, but the BBC returned to attempts to replicate the TV series.

Until “Alien Bodies” written by Lawrence Miles was published. This book introduced the Doctor Who Universe to the world of Faction Paradox.

Who are Faction Paradox?

To put it imply, The Faction Paradox, also known as just the Faction, are a time traveling voodoo cult. The Faction live in opposition to the views and beliefs of the Time Lords. Time Lords aim to keep timelines pure and free of contradiction. Therefore, the Faction seek paradox and disorder in time. They wear skulls that are bigger than their faces, because their skulls are bigger on the outside. While the Time Lords are based in Gallifrey, the Faction Paradox mostly claim their home in the Eleven Day Empire – the eleven days “skipped” when England moved from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian Calendar.

While the Faction opposed the Time Lords, they were rarely direct enemies of Gallifrey. Instead they tended to manipulate and take advantage of factors effecting the Time Lords. In particular, with the Faction Paradox we see also the first Great Time war.

This is not the same Time War we see in the TV series between the Time Lords and the Daleks. Instead, in this earlier war we know the Time Lords will be eventually fighting a war with an unknown enemy. While this war has not started yet, elements of this future war are drifting backwards into our present time. The Doctor purposefully tries not to find out too much about this war, in particular who the Enemy is. By doing this, he hopes of keeping the war a hypothetical reality, rather than a pre-determined future.

However, the Doctor was unable to avoid the technological changes the impending war would bring. For example, the Doctor begins to see the development of future sentient and humanoid TARDISes. While still being a time and space vessel, carrying Time Lords within them through the vortex, they appear as people. Able to hold conversations and physcially walk, they are both time ship and companion in one. Eventually, the Doctor rescues one humanoid TARDISes from being sent to a breeding camp, drawing parallels with slavery imagery.

Faction Paradox leaves the Mainstream

Faction Paradox continued to be a major theme in Doctor Who books up until the release of The Ancestor Cell. This story ends with the Faction Paradox invading Gallifrey. Subsequently, the Doctor destroys Gallifrey to prevent the war (They got better).

Controversially, Peter Anghelides and Stephen Cole wrote “The Ancestor Cell,” not Lawrence Miles. Miles created his own “Faction Paradox” spin off series of books, comics, and audio plays in response. This series continues the concepts he created in “Alien Bodies,” in being explored in the way he had planned.

However, Miles does not have the rights to directly reference Doctor Who concepts. So instead of the Time Lords, we have the Great Houses. Instead of the TARDIS we have “Time ships” And instead of the Master we have the “War King.” And through the “War King” we get to know Lolita.

Who is Lolita?

Faction Paradox as a series has to be coy, as it is not able to directly reference the Doctor Who series without breaching copyright. But it is still able to use the concepts Lawrence Miles created, including the sentient humanoid TARDISes.

Lolita, originally known as Lillith, is one of the first of these sentient Time ships. While she was originally said to be bonded to the War King, how much he actually controlled her is unclear. In “Toy story” she states she chose the dangerous looking Time Lord to flee with prior to becoming humanoid. She also says in this story that some of her adjustments to become human were due to her own choices, not the Master.

However, as she realizes her power of sentience she flees Gallifrey to develop her own plans. She attempts and fails to form an alliance with her sister, implied to be the Doctor’s own TARDIS. The Master then brings her back to Gallifrey, to ally with the Time Lords.

However, Lolita does not feel any connection to any side in the war. Instead, Lolita decides to become history itself. She starts by consuming most of the Faction Paradox inside her internal dimensions. She thenputs herself in various points of history, guiding human history to her own whims. This includes becoming Queen Charlotte, consort to King George III of England. In modern times, her new persona became Lola Denison, Congresswoman for the State of Arizona.

Lola Denison – Path to the White House

Lola Denison was originally a Republican, was criticized for her Libertarian beliefs, and became an independent. Matt Nelson, former Democrat and Presidential candidate for the new Radical Party, sees a common vision, and invited her become her running mate. She accepts this offer, and gains prominence in the campaign due to her direct speaking. However, during this time young women connected to the campaign were found dead, drained of blood. Rumours developed that Nelson was a Vampire, killing these women.

Nelson did win the election, and was inaugurated as President, with Denison inaugurated as Vice-President. However, the rumours of Nelson being a vampire lead to him being assassinated shortly after inauguration. Thus, Lola Denison, really Lolita, really the Master’s TARDIS becomes President of the United States.

Immediately upon becoming president, Denison places restrictions on the media to avoid any space for dissent. Her main policy involved developing energy independence by drilling into the Earth’s Core. While the story does not directly reference Doctor Who, this plan is similar to “Project Inferno” which the Doctor sees results in the destruction of a parallel world in Inferno.

End of Lolita

Eventually the combined forces of the surviving Faction Paradox Members, the Master and the Osirans are able to defeat Lolita. However prior to her defeat, she is able to entirely consume the Master and taking full control of Gallifrey. Only a trap left by the Master allowing her few remaining opponents to unite against her prevents her ultimate victory. A peculiar statue of pure black Onsidian in the shape of a beautiful woman is all that is left of her at the conclusion of her battle.

And thus ends the story of the only truly evil American President, ever seen in any form of Doctor Who fiction.

Related posts:

Doctor Who

Looking Back – The Doctor Who Movie

The Doctor Who movie (1996) was meant to launch a new series, but didn’t. Nine years later the series returned successfully. Why did one attempt succeed so well, and the other fail to start?

Published

6 months agoon

October 25, 2024By

J M

The Doctor Who Movie (1996) was the first completed attempt to return the classic Science-Fiction Series to televsion in seventeen years. In 1989, the Doctor (as played by Sylvester McCoy) and Ace (played by Sophie Aldred) walked off to the TARDIS to have further adventures, but not to be seen again.

And that’s how it remainder on screen for the next eight years. Off screen, many things were happening. Doctor Who Magazine continued making comic strip adventures for the Seventh Doctor and Ace. Virgin Publishing gained the rights to create the very successful “New natures” series of books. Unofficially fan groups and production companies created short movies and audio series which attempted to fill the need new Doctor Who content.

Also behind the scenes were discussions around a Doctor Who movie. Discussions around a possible American co-production for Doctor who commenced in the 1970’s. In the 1980’s Walt Disney Corporation attempted to purchase the entire franchise in the early 1980’s. In 1992-1994 the BBC and Steven Spielberg’s production company had intense negotiations about a new co-production. This developed into a rebooted series, disregarding the previous series. Instead, the story line featured the Doctor searching for his long lost parents while eluding his half-brother, the Master. This original plan changed again into becoming was eventually changed again to be a single ninety minute film made for television, continuing directly from the 1989 tv series.

The movie was completed and broadcasted in 1996. This movie remained the last official piece of Doctor Who being broadcast from 1989 until Christopher Eccleston appeared as the Doctor in 2005. However, it was never meant to be that way. Instead the movie was hoped to lead to further movies, and potentially a series co-produced across England and America.

So…why didn’t it? Why did this attempted relaunch of the series in 1996 fail to lead to anything further? Why did the relaunch in 2004 result very quickly in a successful series which has continued until the present day?

These were the sort of questions I asked myself after a recent re-watch of the movie. By the end I could see a fairly good idea of why the movie failed to completely relaunch Doctor Who for the modern era.

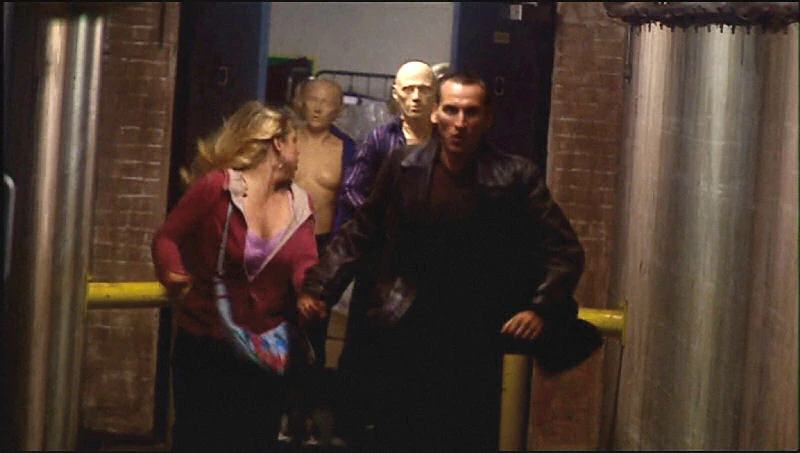

Plot Summary

The movie begins with Sylvester McCoy’s Doctor en route to Gallifrey with the remains of the recently exterminated Master. The Master, surviving as a snake like creature, forces the TARDIS to land in San Francisco. After the Doctor is shot by a street gang, he appears to die at the operating table of surgeon Grace Holloway (Portrayed by Daphe Ashbrook). Later that night, the Doctor regenerates into the Eighth Doctor (Played by Paul McGann). In his new form, he must join forces with Grace to stop the Master, who is attempting to regain his physical form.

Respose – Visuals

The sets are so detailed, and the picture so clear. It looks more cinematic in its detail than anything the series had provided thus far. I love the classic series, but visually they cannot compare to the opening shots of this movie. And that hits you as you start watching it. But that’s an American co-production for you-even their worst television series look better than anyone else’s television.

Initial Fan Reaction

Not this is not the worst television series. It’s not even the worst doctor who story, and it’s surprises me how much hate it gets. I have watched all existing Doctor Who stories, and only ever hated one story. I have found some stories boring. Others I find had plots that didn’t make sense. However, I never hated them and often could find something to enjoy.

However, for a long time, the fan community hated the Doctor Who TV movie. The TV series “Queer as Folk” joked that Paul McGann’s incarnation of the Doctor didn’t count. There was substantial criticism of the romantic references between the Doctor and Grace. When a series failed to materialise, a later planned relaunch suggested forgetting the movie ever happened.

So I re-watched the TV movie aware of the stigma but also not easily hating anything. And, to me, it’s not a horrible story, but it’s not a great story either. If this story had been in the middle of a series, it would be a completely acceptable standard story. The movie in this context would be an acceptable filler story, not a masterpiece.

But this story needed to be impressive, not just average. New audiences needed to be won over by the story on first viewing to for a series to proceed.

This shows partially why “Rose”was successful in comparison. The TV Movie needed to get everything perfect first time. “Rose” in comparison just needed to get people to gladly watch one more episode. “Rose” could build an audience, the movie needed to win an audience. The movie needed to get everyone demanding more episodes. It needed to attract not just fans, but newcomers to the series as well. And the film is not strong enough to achieve that.

Cons – No Central Character to Follow

I wondered while I was watching this – who are we meant to be following in this story? The first voice we hear is the eighth doctor giving an opening narration, but he doesn’t physically appear yet. The Film focuses instead on a largely silent Seventh doctor, until he is shot by a gang. Shortly afterwards, he changes into a new person without explanation. Fans may know this is the same character. New views to Doctor Who would be entirely lost.

Of course, the other human characters are easier to identify with. But Grace is introduced long after the seventh Doctor is shot. Change Lee, who witnesses the Doctor be shot, is a better choice for audience surrogate. He first meets the Doctor when he arrives on Earthis involved in the story from as soon as the TARDIS lands until the end of the story. However he spends most of the story allied with the Master. Potentially this alliance to the Master the story could have worked if he was the central character.

Change Lee’s story would be of being a gang member meeting an alien and helping him restore his bodies. Over time Chang could slowly start having doubts, before realising he is supporting the wrong Time Lord. This would allow better audience engagement for people unfamiliar with Doctor Who. However, the film instead focuses on Grace and the Eighth Doctor. By doing this, most of the first fifth of the film does not feature the focus characters.

Monsters vs the Master – a bad choice

While the Master is a long term villain in Doctor Who, he rarely works alone. In most Master stories, he mostly he works with alien allies, monsters, or robot companions.

The Master is an odd choice for a launch story. I understand the character is affordable as a villain, just requiring an actor, no monster design required. But the Master works better when he has a bit of force behind him. The Master is more of a threat when they have a power behind them, compared to the Doctor operating alone. Having the film just be about two duelling time lords, also leads to one further problem.

How is the Doctor a Hero?

The Doctor is usually our hero, in the movie as he was in the TV series. His name is the title of the movie after all. Once he regenerates, the new Doctor provides massive information dumps to Grace to introduce his character to all of us. But once we learn who the Doctor is, what does this movie say he does?

He saves the Earth! And what does he save the Earth from? His own TARDIS! Which is threatening the entire Earth because the Master left it open. And the Master is only on Earth because the Doctor accidentally brought him there.

Other stories have the issue of the Doctor only solving a problem he created, like this Movie does. However, the movie, in wanting to launch a series, needed to not have problems.

For a familiar fan, you know this is another episode in the ongoing fight between the Doctor and the Master. For a new viewer, though, Earth is just a casualty in a feud between two aliens. Instead of being a hero we need, Earth would have been better off without either the Doctor or the Master arriving. Therefore the Doctor’s actions come off as careless, resulting in deaths and the near destruction of Earth.

What happens next?

At the end of the movie, I wondered “Would I enjoy a series continued from this movie?”

I’ve asked this before, with varied answers. Sometimes I think a new series based on the TV movie would be exciting. Or sometimes I feel a series would esemble other nineties Sci-Fi like the X-Files, and I think I would not enjoy. But this time I realised, I have no idea. Because I have no idea what the series based on this would be like.

The main villain is (apparently) dead. Grace is choosing not to travel with Doctor for a reason I still don’t understand. Perhaps the writers did not want to bring in a new companion if they weren’t certain if there would be an ongoing series. However, other companions had left without explanation, such as Ace in the seventh Doctor era. We’ve got the Doctor traveling without a reason. All the movie has said about his motivations so far is that he transports dead Gallifreyans to Gallifrey.

Potentially the next episode could be nothing to do with this story, using new characters and settings. However, this would mean the next episode would need to completely reintroduce the series again. Alternatively, if it wishes to keep Grace and other concepts of the series, any such episode would need to copy a lot of the TV movie. The doctor is would be drawn back to San Francisco to fight an alien menace and see Grace. While this could end with Grace joining the Doctor, it would otherwise be the same general story outline of the first movie.

Not knowing what will happen next can be exciting. Literally having no idea of what the purpose of the characters you are watching is, is not .

The immediate follow up to the TV movie in other media, the Doctor Who Magazine Comic Book and the BBC Book series, both chose to avoid this problem by immediately sending their version of the Eighth Doctor to places the classic fans would be familiar with: Stockbridge fighting the Celestial Toymaker in the comics, and visiting each of his previous incarnations in the book series

What would have been better if the story ended with the Doctor showing Grace and Chang Lee his home planet Gallifrey on the scanner, and saying “Let’s go!” The next episode would still need to be entirely different from what we had seen before, but this way would build on what has happened before, and give viewers an idea what to expect for the next one, what the Doctor does, and have something to get excited about. And excitement means we want to see the next movie, rather than would merely accept it if it arrived.

What Rose Does Right

So with that in mind, what did “Rose” do right? Why was Rose an instant hit, and the movie was not?

As mentioned before, Rose had the benefit of not having a lot riding on it compared to the movie. No one needs to completely decide whether or not they like Doctor Who by the end of “Rose”, because there are another twelve episodes coming either way. However, “Rose” succeeded regardless.

Partly that was because they did choose to focus on the character of Rose, a fairly easy to understand earth woman. This focus only really shifted towards the Doctor towards the end of the first series, and then once the Ninth Doctor regenerated the focus returned to her. While this lead to complaints of “Rose Show featuring the Doctor” this method was successful in appealing to new fans. If someone had never watched an episode of Doctor Who before, they would learn everything you need to know through Rose, gradually and naturally, without need for info dumps of the kind the TV Movie had in abundance.

This method of introducing the series was used successfully twice before. First we learned of the Doctor through regular schoolteachers Ian and Barbara in 1963, and to a lesser degree we learn of the Doctor through regular earth people the Brigadier and Liz Shaw in 1971.

There was also a clear focus on monsters from the start. Some of them weren’t that amazing, but they had a look which got people excited. The Doctor has a purpose and motivation – to defeat the Autons and save the day. In “Rose”, the Doctor saves the Earth. What he does is save people, not just fixing up his own mistakes. And knowing this is the Doctor’s purpose, we have an idea of what he will do next, creating excitement for the next installment.

Final Thoughts

So, the movie was never terrible, but a good looking production with many problems. It’s big success is showing the later relaunch what not to do which later production teams learnt from. And by bringing us a new Doctor, there was a spark in fandom which may have kept it going for as long as it did, leading to creations such as Big Finish audio series featuring the Eighth Doctor still continuing to this day.

Doctor Who has had a larger amount of output post hiatus than most other stories. Usually there’s a bit of excitement for a few years, then people move onto different things. I noticed in the lead up to the new series in 2004, there was a significant winding down in fan interest, with the BBC Book series slowing production, and Big Finish trying to permanently free itself from regular continuity with the assumption that there would be no regular continuity to ever return to.

Could Doctor Who have survived from 1989 to 2004 relying on only novels, and comics to sustain their fandom? Thankfully, we’ll never ever find out.

(3 / 5)

(3 / 5)