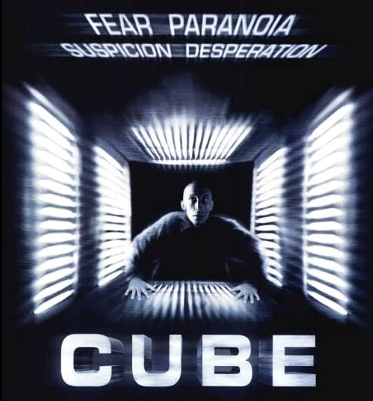

Cube (1997): Trying To Solve a Great Puzzle of a Film!

More Videos

Published

2 years agoon

By

Wade WainioVincenzo Natali’s Cube remains a brilliant film yet, for me, it never comes across as overly smart. Basically, a dumb-ass could perfectly enjoy this film and understand most of it. In fact, it still works out if you don’t fully grasp the whole thing because that puts you closer to the anxiety-inducing and puzzling nature of the main character’s predicament. Trapped inside some interlocking, cube-like rooms with deadly traps, any potential survival deduces a pattern, to escape, lest they stay trapped indefinitely (until the last days, perhaps?).

The group begins to go mad, of course, but it seems the average viewer might understand the reasons (at least some of them). The fact that there are number code patterns is also a brilliant, built-in method for describing the room and its objects in shorthand, rather than relying solely on disorienting visual cues. Granted, I can’t personally follow the mathematical patterns hinted at in Cube, but I’m at least smart enough to grasp that they are there.

Also, as the drama increases between the characters, it’s almost like the frequency of tremors increases dramatically, even if they don’t; The viewer will feel that tension between the personalities, with themselves frequently being triggered instead of triggering the literal traps. We don’t need to see the room boil with steam to know tensions are boiling hot. We don’t need to see flames to get a sense of their inner and outer hell.

Cube unlocks the human puzzle at the center

Overall, Cube“looks at the complex, destructive nature of the human mind, which is its own room of “never enough.” Even when there’s a solution in sight, it’s never quite in sight enough, is it? The story also examines some archetypes, including the ones we might toss onto the characters. For example, when I see the apparent finalists of the Cube contest, I am tempted to observe five (perhaps) interchangeable archetypes between the characters: a reluctant leader, a nerd, a child genius, a wildcard, and a self-rationalizing brute (an antagonist who is chaos cloaked in order).

The man is David Worth (David Hewlett), the woman Joan Leaven (Nicole de Boer), the child Kazan (Andrew Miller), the wildcard Dr. Helen Holloway (Nicky Guadagni), and the brute Quentin McNeil (Maurice Dean Wint). When I say “interchangeable” I mean that all of these characters end up mirroring elements of each other’s traits at some point; they all have sparks of intelligence, wildness, childishness, and angry/violent potential. So, basically, it isn’t just Quentin who you might want to be held in place with restraints because they can all end up at each other’s throats at some point. The fights are really a key element of the story, rather than aspects that seem tacked on to increase the death factor.

More common ground between the Cube characters

As Cube progresses, each character adopts a wide variety of attitudes and responses. Each character has moments of intelligent, adult-like reasoning, but each cube room subdues them and threatens to bring out their proverbial inner children. They also end up interrogating each other. It’s also plausible that there are some elements of the Seven Deadly Sins: Pride, Lust, Gluttony, Greed, Envy, Sloth, and Wrath. Ultimately, Cube solves the puzzle by what amounts to a process of killing the child, who almost seems to emerge to face some sort of Judgment Day.

Then again, I could be wrong about some of the things I have set down here. Really, that’s part of the intelligence in Cube. So much is open to interpretation. Things that sound outlandish to me might sound plausible to others, and vice versa. We do know that this giant puzzle is twisted and strange, and maybe one of the unspoken plot devices here is that the characters are truly just characters, or pawns, put through crazy circumstances and contractions for the audience’s own questionable amusement.

What are your thoughts on Cube? Let us know in the comments!

You may like

Doctor Who

Identical: Yes. The Same: No – Exploring the World of AI Reconstructions in Doctor Who

Published

2 weeks agoon

March 19, 2025By

J M

The second half of 2024 was a bit of slow for Doctor Who news. Ncuti Gatwa’s first season finished in June, and the Christmas special was months away. Comics and audio plays continued, and a Blu-Ray set of Season 25 was released – but that was all.

However, what was new and exciting was a spate of unofficial recreations of missing Doctor Who stories from the sixties. Re-animations of missing stories have occurred previously, both officially by the BBC and unofficially by fans. However, animation production time means it’s rare to have more than a few episodes a year. However within the space of six months, forty-four recreated episodes were released, with the promise of more to come.

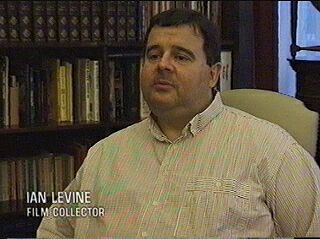

The reason how so many stories have been released so quickly is artificial intelligence (AI). These reconstructions are Generative AI, funded by professional songwriter, film producer, and fan, Ian Levine. This decision to make Doctor Who AI Reconstructions, to put it mildly, has been controversial online.

But is it worth it, in order to having otherwise missing stories returned to us? I’ve examined many of these Doctor Who AI reconstructions, and the discourse around them, to find out.

In Brief – Missing Episodes

A decent proportion of Doctor Who’s earliest years shockingly does not exist anymore. Doctor Who is one of the BBC’s biggest revenue raisers, and most famous show around the world. However it was not always the case.

When Doctor Who first began in 1963, the idea of keeping media was not really considered. Home video did not exist, and would not exist for two decades. Repeats were rare, due to the costs at the time to store old material and pay people involved in them. Also, old film presented a fire hazard. So it was often disposed of.

Despite this, Doctor Who is fairly lucky compared to other series. Firstly, fans at the time recorded the audio of each story. This means even the first ever Christmas Special – “A Feast of Stephen,” never broadcast internationally or repeated, still exists as an audio.

Doctor Who is also lucky because of only six seasons are not complete. In addition, of those six seasons, only half are missing only episodes from one or two stories. This allows us to get a feel for the early years of Doctor Who in a way fans of other series, like “Quatermass” and “The Avengers” aren’t able to. And part of the reason most of these early seasons survive is due to Ian Levine.

Who is Ian Levine?

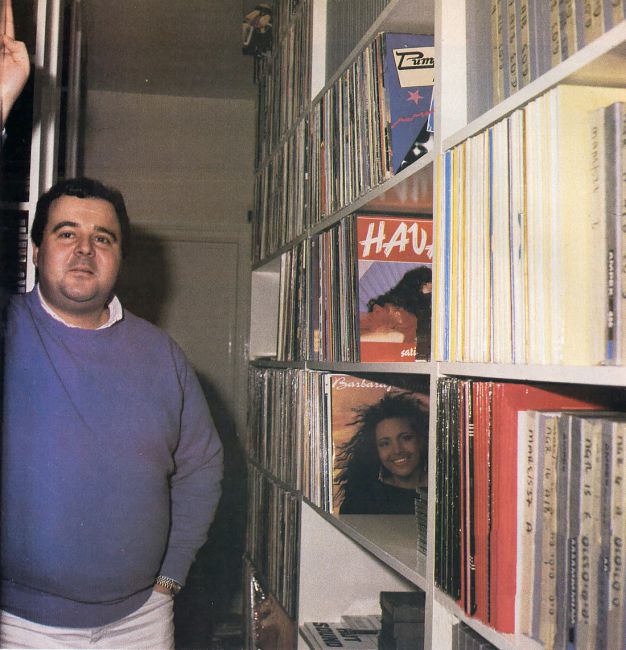

Ian Levine professionally is a songwriter and DJ. He has written and produced records connected to such bands as Take That, Pet Shop Boys, Bananarama and Bucks Fizz. His total sales exceed 40 million records.

He is also well known as a prominent Doctor Who fan. There are many prominent Doctor Who fans. The series from 2004 onwards has been largely made by prominent Doctor Who fans of the 70’s and 80’s. Many of these fans contribute to Doctor Who in official ways. For instance, many older fans have written books, or audio plays. All three showrunners for the modern series would be considered prominent fans from the nineties. For Ian Levine, his main contribution is seeking to find and restore missing episodes of Doctor Who.

This work started in 1978 where Levine reportedly requested the permanent halting of old episodes of Doctor Who. At the time the idea of home video was being considered, leading to more reasons to keep old film. Levine also claimed to have rescued the first ever Dalek story from being sent into a furnace. Following this, he began purchasing private copies of the remaining stories, and attempting to return them to the BBC.

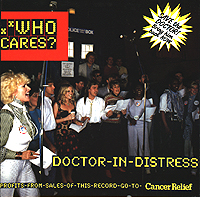

He also connected with the Doctor Who Production Team of the eighties in other ways. This included composing the theme tune for the spin-off series “K-9 and Company”, and the protest/charity album “Doctor In Distress.” His was also consulted about continuity during seasons eighteen to twenty-two.

However, he also gained a notorious reputation as obsessive in an unappealing way. During the 1985 Doctor Who hiatus, Levine was encouraged by Producer Jon Nathan-Turner to use protest the decision. Levine argued against the decision on television, and smashed his television with a hammer, and inviting newspapers to photograph it.

So he is fan who has both done great things, but also sought notoriety and negative attention.

More recently, Levene has worked with animating missing or incomplete episodes. This started in 2010 with “Mission to the Unknown.” This was not allowed to be shared or sold due to it being made without BBC authorization. In 2013, Ian hired an animated reconstruction of the unfinished story “Shada.” This version used pre-existing footage and new audio to create a finished product he hoped could be licensed. However, the BBC chose not to. Instead they made their own animated version that was released four years later.

- Join the Doctor (Tom Baker), Romana (Lalla Ward), and K-9 (voiced by David Brierley) as a visit to a Time Lord living incognito on Earth leads to a desperate race to a distant prison planet

- A BBC strike halted filming of this never-broadcast Baker six-episode serial written by “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” author Douglas Adams

- Christopher Neame, Victoria Burgoyne co-star

Last update on 2025-03-16 / Affiliate links / Images from Amazon Product Advertising API

Subsequently, Levine made comments regarding Jodie Whittaker as the first female Doctor which were deemed by many to be sexist. Levine responded by publicly quitting the fandom, though later created his own private Doctor Who Facebook group.

This group has now become the location where his AI recreations he has funded and received donations for are shared.

The Doctor Who AI Reconstructions – How to Access

The Facebook Page: “Ian Levine’s Facebook Group” requires an agreement to two questions to join. Firstly, you must agree to respect the right to criticize Jodie Whittaker. Secondly, you must recognise this is Ian Levine’s group for sharing his opinions on Doctor Who. Agree to all this, and you’re allowed in.

Inside the group, Levine has shared around twenty videos. This includesall of “The Dalek Masterplan,” “The Massacre,” and “The Savages.” However for the remainder, you must make a donation of fifty pounds, to become a contributor to the series.

Once your donation is confirmed, you are authorized to join the separate contributors group, for contributors only. This is where all the current videos being made are released.

Except…. None of these videos are unavailable privately. Ian Levine has placed them all on Youtube. They are unlisted, so they cannot turn up in either a Google or YouTube search. However, if you have a direct link or URL to them, they are accessible to everyone. Unlike other systems like Patreon which restrict content to only certain subscribers, nothing stops these links being shared elsewhere.

And of course, these links are shared. In response, Levine has issued threats and warnings against other Facebook groups and leakers trying to destroy his vision. In his group, people support him and join in denouncing those who criticize his work or mock it. People outside the group in response denounce Ian Levine and his supporters.

One thing I hate about internet culture is the push for tribalism. This is the idea we are joined in a selective tribe and must fight the rivals to connect. Over time the views become more strict in supporting your own tribe, and rejecting the opposition, and the middle ground is lost.

In the case of Ian Levine’s group, this is best shown by the view of alternative animations of missing Doctor Who stories. All of these are seen as not as good as Levine’s AI reconstructions. Levine’s reconstructions are seen as the only correct way Doctor Who is meant to be.

Initially Ian Levine’s AI project aimed to complete the ten missing stories not completed by the BBC. The initial project recognised the slow time it took to animate missing stories, and focused on stories that were difficult and costly to animate with people. Very soon after, however, Levine denounced many of the prior animations as “Silly Scooby Doo Cartoons.” The project was quickly extended to include stories previously animated by the BBC. Levine’s argument appears to be Levine’s objections to story changes animation had included. These included adding a surprise image of the Master in “Fury from the Deep”, prior to his debut appearance. Given Levine’s history of making things for the BBC, with the hope the BBC would license them, there have been rumours Levine initially was hoping the BBC would license some of his AI recreations, which has not come to pass.

Levine presents his animations as the most authentic way to view the missing episodes. Therefore appreciation of official animated reconstructions are not allowed. A poster saying they enjoyed the animated version of “The Celestial Toymaker,” was informed by Levine tht anyone who enjoyed the animation was unwelcome. Common responses of new animations being announced are people accusing the BBC of ruining another story. When Levine had a fault pointed out in one of his stories by Frazer Hines, who played the second Doctor’s companion, Jamie, Levine’s first response was to accept that the animation had limitations, but insisted it was still better than any animation the BBC has made. Most of all, posters all reinforce the message that AI reconstructions are the true version of the lost stories and the BBC are fools for not paying for them.

- The Celestial Toymaker sees the Doctor and his companions separated when they come up against the Toymaker

- While the Doctor plays the Trilogic Game, Steven and Dodo are forced to play their own seemingly childish, but ultimately dangerous games, with the aim of being reunited and getting back to the TARDIS

- Who will be the first to make a false move in this battle of wits, and will the TARDIS ever escape the Toymaker’s snare Fans of Doctor Who have long lamented the loss of the original 1966 master recordings of all except one of The Celestial Toymaker

Last update on 2025-03-16 / Affiliate links / Images from Amazon Product Advertising API

In response to this, or provoking this, depending on your point of you, external Facebook groups and YouTube channels are highly critical of the AI reconstructions. Some videos see them as threats, preventing the BBC from every investing in animation involving real people. Some hav dismissed the project as a scam.

So with such strong opinions on both sides, it’s time to actually watch them.

The AI Reconstructions

My first response on watching is they’re not that bad, but they’re not that good. Animation varies wildly in quality from story to story, making it hard to tell an overall trend towards or away from quality. However there are some good examples of how to recreate a story. “The Massacre” and “The Dalek Masterplan” for instance are incredible to watch. “The Savages” on the other hand is laughingly bad.

I chose to mostly focus on the stories not yet officially animated, so as to judge these stories by their own merit rather than compare to other animated versions of the same stories. However, it’s interesting the similarities that occur between the official animations and AI reconstructions. Non human characters (Particularly Daleks) look and move great, but people largely do not.

Animating People

Across most forms of Missing episode recovery, whether AI or human drawn, the difficulty is always animating people to show emotions and movement. Many of the official BBC animations often leave characters looking like stick figures bobbing up and down.

However one of the key things the official reconstructions provide is consistency. A human being develops a pre-existing model for characters, and because of this, these characters stay consistent over time.

AI on the other hand appears to forget things, or lose focus unless properly guided. People’s faces can change dramatically from shot to shot to the point, as in “The Savages” characters can be unrecognizable. This means, unlike with official animations, I often had to follow a story summary to figure out what was going on.

AI also forgets smaller things that make people seem human. In “The Highlanders” for instance the Doctor’s companion Polly does not blink for most of episode one, despite being in shot. This is a small detail, but throws the story into the uncanny valley – characters involve look like people but they feel wrong based on how they act.

Movement is a struggle for all reconstructions because human movement is difficult to animate. Once again, “The Massacre” demonstrates small examples of movement than seem fluid, particularly in the first episode. “The Savages” on the other hand has main characters seemingly to perform scissor jump spread legged when the script call on them to walk.

How the animation occurs

Having watched many of these animations, some of means AI generated these reconstructions became clearer. A lot of these animations, especially some of the later ones, do not actually generate much new material, instead using existing material in different ways. The First Doctor saying goodbye to Susan in the TARDIS, from Episode 6 of the Dalek Invasion of Earth, for instance is frequently re-used. This scene is redubbed multiple times in the reconstructions, when a missing story needs a scene of William Hartnell standing alone in the TARDIS.

Another method is using the telesnaps, and slightly animating the mouth and face. This creates a sense of fluidity and movement, but a very limited one. This is particularly noticeable in the Space Pirates. The resconstructions rely on switching between static photos of one cast member with mouths moving. On the one hand, this is no worse than the telesnaps, but the telesnaps were aware of their limitations, so often would use narration or subtitles to fill the gaps. However these reconstructions are presented as the most life like renditions of the missing episodes. As the original story did not have subtitles or narration, therefore, they are not allowed. As a result the story is incomprehensible.

Benefit – it exists

But despite the complaints, there is a significant benefit in these reconstructions. And that’s the fact that they exist.

Currently nine missing stories have not been officially animated by the BBC. I would love for all missing stories to be animated. However, the reality is most of the stories remaining might be too costly to animate.

Of the nine stories, six are pure historicals – stories with no science fiction elements apart from the TARDIS and its crew. These stories tended to have a larger number of human characters than stories with monsters, and a human being with their range of emotions is harder to animate than a Dalek.

Historicals also tend to have more detailed and complex scene change. A story in the future can replicate cold, grey corridors throughout a space colony. Historicals however must recreate significant locations in the world at particular times in history. Having to recreate 15th century France, for instance, is made up of multiple distinct locations. This makes historical stories more time consuming and therefore costly to animate. Therefore, despite stories being reanimated for almost twenty years now, the total number of historical episodes animated have been two – both missing episodes of the Reign of Terror.

For the remaining three stories, the limited human cast and isolated space station locations makes Wheel in Space relatively simple to animate. The Space Pirates, may also be animated as the story focusing mostly on space ships should make some aspects of the design easier to manage.

That just leaves The Dalek Masterplan¸ a massive twelve episode story, with a one episode prequel, where the Daleks chase the Doctor throughout time and space. The cast is huge, and while it is not a historical, the story would require animated sets of ancient Egypt during the building of the pyramids. None of this would be easy to do on the current BBC animation budget.

Therefore, it appears of the remaining nine missing stories, only two are highly likely to be animated.

And this is where AI can play a role. As AI does not rely much people, it means the costs to recreate a story like the Dalek Masterplan is significantly easier and cheaper than hiring a production studio to make it. While the end result is not as good as a professionally animated episode, for stories where hiring professional animations is not feasible, this is one way for people to observe a version of a story we otherwise cannot access.

Ultimately the frustrating thing about these reconstructions is they’re not allowed to be what they are. If they were simply an attempt to make otherwise lost stories more accessible, without any pretention or idea of superiority they would be fine. There are no shortages of fan made reconstructions, which vary in quality, but are all warmly received because they don’t pretend to be more than fan made animations. They are no better or worse than any other reconstructions.

If Levine’s reconstructions were presented with the same humbleness, the response would be more positive. If Leveine would present it as a project, and be accepting of others not needing to accpet them, there would be less retaliation online. But they aren’t presented as a fun way to view a loss episode. The reconstructions are presented as the only correct way to view the stories, superior than any other effort. In fact, he considers the stories no longer lost due to his AI reconstructions.

But by doing so, he puts the reconstructions on a pedestal of perfection. But they aren’t perfect, not by a long shot. By Leveine presenting these as perfect, he ultimately encourages people to notice how they are lacking by comparing to perfection. In comparison, more humble attempts of reconstruction, by presenting themselves as not the best, encourage people to notice what they do right.

So, try to enjoy the reconstructions for what they are. Some are surprisingly good – especially The Dalek Masterplan and The Massacre, and it’s a chance to see stories animated that you may not get to see animated elsewhere. But try to filter out all the rhetoric about how amazing and perfect they should be, and just enjoy them as they are.

(2 / 5)

(2 / 5)

Related posts:

Movies n TV

Wheel of Time A Question of Crimson Is a Political Espionage Delight

Published

2 weeks agoon

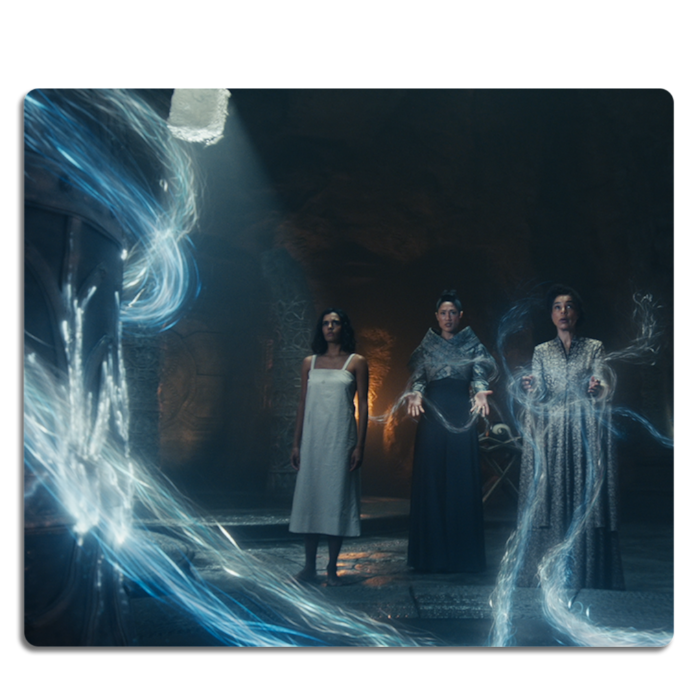

March 17, 2025Episode two of Wheel of Time felt like the beginning of a long journey. Stories are unfolding, lives are changing, and blood is spilling.

Let’s discuss.

The story

We begin this episode in the past with Elayne’s mother, Queen Morgase. It turns out her rise to the throne was a bit, shall we say, cutthroat. So when she shows up at the White Tower, Siuan is concerned.

She might have reason to be, too.

Meanwhile, Rand, Egwene, Moiraine, Lan and Aviendha are in the Spine of The World. As they travel through some of the most breathtaking lands I have ever seen on a TV show, Egwene is plagued with nightmares. We think at first that’s just her trauma working itself through her system. But we soon find out that it might not be that straightforward.

Finally, Perrin returns home to heal after his hand is almost cut in half. But when he gets there he finds the town has been infested by Children of The Light. And they’re looking for him.

What worked

There was something heartwarming in this episode about political espionage and choking religious persecution. And that is Elayne’s relationship with her family.

I have consumed a lot of fantasy content with royal families. And I have never once heard a princess call her mother ‘Mum’. I’ve never seen royal siblings get along. And I have sure as hell never seen a princess have a good relationship with her step-parent.

This was refreshing. Even though Queen Morgase is kind of a horrible person she seems like a good mother. And that’s an unexpected delight.

Of course, this is just one storyline among many. And while this can sometimes be overwhelming, in this case it wasn’t.

I’ll be honest, some of these storylines are going to drag for me. I know this because I’ve read some of the Wheel of Time books and I have an idea that not all the characters exactly pique my interest.

No one likes all the characters. No one likes all the storylines. While I am here for the political espionage between Queen Morgase and Siuan, not everyone likes it. While others might be fascinated with Selene trying to win Rand back, I couldn’t care less.

Having multiple storylines keeps everyone’s attention better. So long as things don’t get out of hand. Things can easily get out of hand. But this seems to be managed well.

So far.

What didn’t work

As I mentioned above, I’m not thrilled with Rand’s story at this point. And while it’s fine to not like a storyline when there are this many to choose from, it’s not fantastic that the one I like the least is the one involving our two main characters. And anytime we were with the team at the Spine of The World, the only thing that brought me joy was Moirain’s hat. It reminded me of Stockard Channing’s hat in Practical Magic.

The problem is that Rand is Charlie Brown with controversial magical powers. He is boring, serious, and pessimistic.

And yes, I understand that he has a heavy emotional burden and he’s the Dragon Reborn and that’s quite taxing and all. But let’s be fair, there isn’t a single person in this show that doesn’t have a heavy burden. And most of them manage to be fun occasionally.

All that being said, this episode of Wheel of Time did exactly what it needed to do. It set up conflicts at each of the three locations. It established emotional ties between the characters and the events. And it established goals for everyone.

This was, in short, a solid episode. Not groundbreaking, not mind-blowing or life changing. It was simply good. It was entertaining and moved the plot forward.

Well done.

(3.5 / 5)

(3.5 / 5)

Wheel of Time is back for season three. There are mixed feelings regarding this. Last season, there were some serious pacing issues. And some serious sticking to the book’s storyline issues. But we’re two seasons in, and we don’t give up so easily. So let’s dive into episode one, To Race the Shadow.

By the way, I highly recommend watching this episode with the subtitles on. You’ll see why.

The story

We begin this episode with Liandrin facing a trial of sorts for her rampant betrayal. She does her best to gaslight her Aes Sedai sisters into thinking that Siuan Sanche is the real traitor.

When that doesn’t work, she reveals how many Black Aes Sedai have actually infiltrated the tower.

Spoiler, it’s a lot.

In the aftermath, our whole team gathers to drink and enjoy one night of relaxation before they head out to the Tear to form an army for Rand. All is going well until they’re attacked by myriad creatures and a sentient axe.

What worked

This episode was long. It had a run time of an hour and eleven minutes. And a lot of that run time was spent in heavy dialog scenes.

Fortunately, these were well-done scenes.

If you’re going to have a lot of talking scenes, there are good ways and bad ways to do it. Last season, we saw lots of examples of the bad way to do it. But this episode did it well. For one thing, other things were going on while conversations were taking place. The characters are drinking, playing games, walking through an interesting city. And the scenes themselves didn’t stretch out. They weren’t repetitive. We heard what the character had to say, then we moved on.

It was also nice that the point of these scenes wasn’t just info dumps. We had character development. We had romantic interactions. We had plot development and foreshadowing.

Overall, this episode felt like what it was. A moment of calm before a storm.

Taking a step back, I’d be remiss if I didn’t address the fight scene at the start of the episode. Because it was epic.

The magic looked amazing. The martial arts that went along with it looked fantastic. The costumes were beautiful. It was just incredibly fun to watch.

More than that, it was emotional. We lost some characters in that fight that were important. And it was clearly emotionally shattering for many of our characters, who found themselves betrayed by people they trusted.

So many of them.

It was a great way to open the season.

What didn’t work

Despite that, this episode wasn’t without its flaws.

First off, there were a lot of dialog scenes. And they were good scenes, as I’ve already discussed. But it was one after another after another. And when your episode is, again, an hour and eleven minutes, it’s maybe a little much to have so much chit-chat. Couldn’t some of these conversations, important as they were, have been moved to maybe another episode?

Finally, I want to talk about Egwene’s travel through the arches.

I feel like maybe there were some deleted scenes here. Because there must have been more to that visit than what we saw, right?

We could have seen Egwene battle Rand. That would have been badass and emotionally devastating. We could have seen her with a quiet life with Rand back home at the Two Rivers. We could have seen anything except for the quick clip of Rand in a bloody river, followed by Egwene being shoved back out in a bloody shift.

No products found.

Bad job. But at least it wasn’t an extended scene of Moiraine collecting bathwater, and then taking a bath while looking sad. If we’d started this season with another scene like that, it might have broken my brain.

Amazon dropped the first three episodes at once. So we’ll be back soon to talk about episode two. See you then.

(4 / 5)

(4 / 5)