Interview with Martin Takaichi

More Videos

Published

2 years agoon

By

Leather Snow

Free League Publishing recently released Tales From the Loop, a sci-fi adventure board game based on the popular art book by Simon Stålenhag. I had the opportunity to interview Martin Takaichi, the lead designer of the game. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us a little about yourself, and how you got into game design?

Well I’ve been tangentially involved with gaming since I was like 8 or 10 or something, when I started playing games, and then I started working in game stores and coming into contact with a bit of the game design scene in the 80’s. I actually started professionally designing games about 10 years ago now? I started helping out, since I’m friends with several of the Free League members, they asked me to help out with playtesting and a few other things, kinda brought me in for small pieces here and there. When they were going to make the Crusader Kings board game they asked for my help since I have more board game experience than they do. So they took me in there as kind of a consultant, basically, so I helped them create the foundations, the core of the game, on which Thomas could innovate on and make all the details. And then of course after that they asked me if I could make a Tales From the Loop game, which, yeah, I could, I wanted to. The era of the art books is very much of the same time as when I was growing up and a lot of the images are things I recognize, the islands where it takes place are close to where I grew up and I have friends from there, so it’s a very familiar piece of terrain. It was a lot of fun to dig into that and dig into my own memories of the time and spill that into the game.

Were you adapting just the art book, or also the tabletop game?

We discussed what kind of game it would be, and our first thought was to try to make a board game version of the role playing game in a way, but then of course we explored other ideas, like we could maybe make a game where you’re like magnetrine transport, or you might have a one against many kind of game where you have an overlord or mysterious Loop character. So we explored different avenues, at the end we just came back to the thing like yeah, we’d like to try and bring the RPG and put it in the board game format since I mean, most role players I know play board games but not all board gamers play roleplaying games, so we wanted to bridge that gap a little bit. So in the end it was just “Okay, let’s see how close we can get the experience to playing the RPG.” But of course the art book is still the core.

What were the core elements from the art book that you felt were most important to incorporate into the game?

I think one of the most important things about Tales From the Loop, the thing that makes it work, is the juxtaposition of the very mundane, y’know kids in 80’s clothes going to school, and then of course the extraordinary, like the machines, the dinosaurs, the strange monsters. We built the RPG where you have these adventure scenes and then also the at home scenes with your parents or something like that. And we wanted from the start, like we really need to capture that. So that was part of the reason for why we have the parental happiness mechanic, if they’re nice and happy they can give you rides, or if they’re angry you get grounded, and also the system of having chores that you need to do, so it’s not always just going about looking for dinosaurs, sometimes you just have to go and pick up your little sister from daycare or something. That was the key important thing, and then of course just the fun kids on wacky adventures feel too, cause the art book, you know, sometimes it’s fairly wacky, and sometimes it’s very dark, and the Amazon series as well is also kind of leaning more towards the melancholy, slightly dark tones. And we like those, we really do, but for this game we wanted to keep it more springy and happy.

Something that interested me about the is you’re not just gamifying the experience of solving a mystery, you’re also gamifying the experience of being a kid. What were some of the challenges with that, and how did you balance the two?

Since that was one of the foundations when I started designing the game, I was like, “Okay, I want these two things.” It would have been much harder to implement or bring it in later to the process but since we had it from the start it was something where we could continually adjust the balance here and there. But I think one of the challenges of making this kind of game, I think often many games (not all of course but many games) that try to emulate the RPG feel they do it a way that’s, y’know you pull up a card and then there’s a lot of text to read, like, oh this happens and blah blah blah, and there’s a monster or something and there’s flavor text, and then at the end roll this. And that doesn’t really make me feel in character, just makes me read little text and then kinda, “Huh.” And if I play the game long enough I usually just skip the text and go “Okay, what do I need to roll?” So we wanted to avoid that. And really like, how does it feel to be a kid? What’s the thing to bring into the mechanics to create the theme of it? To have the mechanics of the items you pick up, or the chores you need to do, or you need to go home in time, and really have those kind of things create the theme among the players rather than have them on the cards. And it was a bit challenging for us, because you need to find the right balance. But I think in the end for me when I watched people playtest, and you can see usually at the start of a turn they’ve been to school, they’ve heard some new rumors and have some ideas and they say okay we need to go here, and then they huddle up and they have this plan, they’re gonna go over here and do this thing, and then one of them chimes in, “Uh, no, hang on, I have to, you know, mom, she asked me to pick up some things at the grocery store, so I have to go, sorry guys,” and everyone’s like “Oh no!” And that’s the experience, what it is when it really works, and it seems to compel people, people seem to like it. So yeah, I’m very happy.

What were some other sources of inspiration?

Recently of course, there’s been Stranger Things, which has been like a huge thing, and I guess we were fortunate to have been ahead of that wave a little bit, since we managed to- I mean Simon Stålenhag precedes Stranger Things, and our game ultimately precedes Stranger Things- but we got right on top of that wave, we were able to ride it through so of course that’s another modern inspiration. We also have some old Swedish tv series I was watching when I was a kid, but then just the general sense of fun and adventure, something very light, that makes you kind of recognize things from when you were a kid. When we were creating the items for example we wanted to take things that felt familiar to a large population, not just here in Sweden, though we have some Swedish easter eggs in there. We have simple things like bikes and chewing gum and things, tweaking the logos and things to make them fit the universe. So just taking things from our own lives, movies we like.

You mentioned you were working on the Crusader Kings project, how did your experience with that contribute to this project?

I wasn’t heavily involved in the start of that project but it was still very good to get better experience working with a team in a way that I haven’t done before. When designing board games just for yourself and your friends, that’s one thing. The number of iterations that’s required and how you really need to be on point to make sure that everything really works, and even now there are things that are gonna turn up that’s like, if we do this and this thing in the game, and this thing is also happening, it kinda breaks a little bit, cause it’s a complex game. But still, to have another understanding of the requirements needed was very good. And also just producing board games these days is just a big apparatus, with international shipment and everything.

In what ways did the game change over the course of design? What kinds of elements were added or dropped?

There hasn’t been some really major changes, but of course a number of smaller changes, like for example at the start we had cards that if you went somewhere and there wasn’t something special that happened there you got to pull generic cards with mini events depending on where you were. In the end we dropped that. They were fun and flavorful, but they also diluted the experience a bit, so we dropped those to keep the focus on the narrative and the actual rumors. Also the streamlining being done, we simplified the hacking quite a bit. From the start hacking was like a hacking tree and depending on how the machine looked different things happened, and even now I think maybe we should have simplified it a bit more, but still, it’s smoother now than it used to be. Overall I think the core experience stayed pretty consistent from the start. The diary cards, the rumor cards, school cards, it’s been surprisingly stable I’d say. But of course filing down little nubs here and there to make sure there’s no too-sharp corners. We also had for a while, I think actually during the alpha for the Kickstarter, we had specific action sections on the player board. I just realized that’s really not important, we can just have a big pool and you put them there and you do the thing on the board, so small things like that, to just get a better experience.

How was working with Kickstarter? How did that effect development?

Free League has been doing Kickstarter for a while now, we have good experience with it now, but of course it’s somewhat different making an RPG and making a board game. There’s a slightly different crowd, and different kinds of stretch goals you can do, and it’s also different kind of feeling because you run the Kickstarter and you have an almost finished game, and once the Kickstarter’s over you have more of a time pressure, there’s more to complete the thing, you have more of a deadline issues, whereas if you develop it outside of Kickstarter you’re more free to have a little bit more leeway. I mean, we were very happy how the Kickstarter turned out, and we had a great working relationship with Dust Studio, the guys who made the miniatures (well, made the actual entire game, not just the miniatures), so that process has been really smooth. It’s more how shipping works these days, has been more of, I wouldn’t say nightmare, but still it kept me up a couple of nights. Things are slow moving these days, and expensive.

How did the design inform the components? Like keeping in mind how many components you might need, what kind, things like that?

That’s another thing with making board games that are more complex than an RPG. With an RPG of course you have the page count to have in mind, but for a board game there’s more components. For example how much punchboard can we put in the box, and we counted things out. From the beginning we wanted a very thin box, that was our hope, and it kinda swelled out a little. It’s still okay, it’s not too thick, but we would have preferred a thinner box. But still, just counting out “Okay, we want all of these counters, and all of this thing, and that would take this much punchboard, then you know how much you have, and you count out all the items that are needed and then you realize like “Okay, there’s some space left, what can we use for that space?” Another thing, ideally we would like to have had cardboard minis for the machines as well, as a bonus for people who want to have their machines on display or something, unfortunately the available space was just a bit too small, so we couldn’t do it. It’s interesting the different things you have to take into account. But again, Dust Studios were very easy to work with and they helped us out a lot with designing the tray and the insert. I’ve been playing board games for 35 years, so for me it’s very important that if we want to make an insert, either we shouldn’t make an insert at all or it should be an insert that’s actually usable so people don’t just throw it out, because that’s what I tend to do with most of my games, cause most of the time they’re not useful. But here we actually spent some time to make sure that it works and it’s useful. We had a bit of a discussion, we should have miniatures for the kids as well, but in the end we decided against it because the kids, we want them to- I mean the art, that’s Simon’s art for the kids of course, and I think turning those kids into 3d models wouldn’t be as exciting as the machines. We also wanted the machines to pop more on the board, so in the end we went with the two different things, and I know some people, they want all models or all cardboard, not this strange mix, but for us it was important to keep them separate and to make the machines pop.

What was the best part about working on this project?

I think for me still one of the best parts was to go back to [Simon’s] books and really make the connection with my own childhood in a way and then figure out how to capture that feeling, cause when I was a kid and I was with my friends and we had our bikes and you were out playing in the woods or whatever for a few hours and then come back for dinner and just, can we capture that? Just pulling things from that experience and putting it into the game, and especially seeing playtesters getting it like “Oh!” And lighting up, it’s like “Okay, they get it, this works,” so that was really gratifying.

Where do you plan to go from here?

We have ideas of course, since there’s two books to the Loop universe. So far we have Tales from the Loop, then of course Things from the Flood, which is we move the story to the 90’s, and it becomes a little bit darker, they’re teens and there’s mutated strange machines, stuff like that, so that would be interesting. It could be a standalone expansion in a way, like a sequel game maybe, or we could do something else, we could make more smaller expansions like we have now, The Dinosaur and The Runaway, but first off we’re going to wait. We have the retail release very soon here and then we just want to see how people take to the game. So far it seems like people are enjoying it, so if people want more, who are we to say no? We would love to make more games in the Loop universe, just not anything decided quite yet though. But there will be more other games.

Tales from the Loop is out now, you can check it out on Free League’s website here. You can check out the art book the game is based on at the link below. Remember that we are an Amazon affiliate, and if you buy anything from the amazon links provided, we will get some $ back. You can find Martin on Twitter @firebroadside.

You may like

-

Interview with Creative Director Michael Highland: Let’s! Revolution! @ PAX

-

Interview with Game Dev Julian Creutz: Quest Master @ PAX

-

Heroic Adventures Await: An Epic Review of The One Ring Starter Set

-

Into the Odd Remastered: an Ethereal Steampunk TTRPG

-

Blade Runner RPG Starter Set Review

-

Free League Publishing Black Friday Sale Now Until Nov 28!

Gaming

Stygian: Reign of the Old Ones (2019), a Game Review

Stygian: Reign of the Old Ones (2019) is a tactical role-playing video game developed by Cultic Games, evoking Lovecraftian horror.

Published

3 months agoon

April 30, 2024

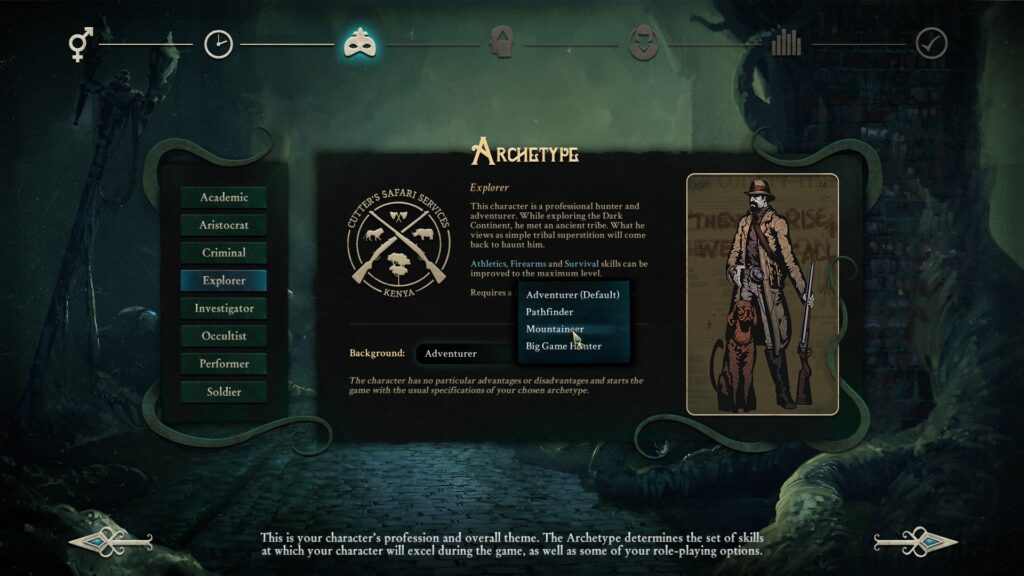

Stygian: Reign of the Old Ones (2019) is a tactical role-playing video game developed by Cultic Games, evoking Lovecraftian and cosmic horror. Published by Fulqrum Publishing, this game is available through Linux, macOS, and Windows. This review will cover the $19.99 Steam release.

The Great Old Ones have awakened, exiling Arkham after the events of Black Day. Design your character and face the abominations of Arkham. Explore the 1920s through a Lovecraftian aesthetic as you unravel the secrets that plague Arkham, facing unknowable cosmic horror and malicious abominations.

What I Like Stygian: Reign of the Old Ones

The depth of character creation starts the game off on the right foot. While appearance has various options, the game provides greater variety in motives, age, and origins, adding different gameplay elements. For example, age reflects lived experience and physical competency. The younger your character, the less experienced but more physically capable. This dynamic requires trial and error to find the best choice for you.

The paper cutout art provides a unique interpretation of a familiar (but stylish) Lovecraftian aesthetic. While not the most haunting execution of the Lovecraftian, it still manages to unsettle and unnerve while maintaining visual interest. That said, if the style doesn’t suit the player’s taste, Stygian: Reign of the Old Ones might leave that player wanting.

While I find the story engaging and the mysteries worth exploring, there’s a massive caveat to that claim. Regardless, if you fancy the Lovecraftian, few care as deeply and express as much knowledge of the genre as Cultic Games in this installment. This love and knowledge shines through in the often subtle allusions and references to the expanded universe. It may earn its place as the most Lovecraftian game out there.

The characters vary in interest and likability, but there’s usually something about them to add to the overall mystery. Naturally, this remains most evident in the companions that accompany the player on their journey.

In terms of horror, Stygian: Reign of the Old Ones achieves notable success. Despite the subjective points of aesthetics, the game brings out the most unsettling and uncomfortable elements of Lovecraftian and cosmic horror.

Tropes, Triggers, and Considerations

With an understanding of the Lovecraftian comes the question of how to deal with racism. Most properties try to remove this context, but Stygian: Reign of the Old Ones recognizes the text and era (the 1920s) with caricatures such as a lunatic in blackface. I won’t say it fully explores these toxic elements, but it’s not painted in a positive light.

Insanity and mental illness play a large role in the mechanics of the game, such as becoming a key component of casting spells. Loosely related, drug addiction and usage are mechanics with varying degrees of necessity depending on your build.

If these are deal breakers, perhaps give Stygian: Reign of the Old Ones a skip.

What I Dislike about Stygian: Reign of the Old Ones

In terms of story, this game is unfinished, leaving many plots, quests, and arcs with unsatisfying cliffhangers. My understanding is that Cultic Games planned to finish the game, but money ran out, and the focus shifted to an upcoming prequel. I imagine the goal is to use this new game to support a continuation. But that doesn’t change the unfinished state of Stygian: Reign of the Old Ones. The beginning and middle remain filled with content, but the final act (loosely stated) falls monstrously short.

While this unfinished state mostly affects content, I did run into game-breaking bugs. From my understanding, these bugs completely hinder progress. Most are avoidable, but some are unlucky draws.

It’s these points that make this a challenge to recommend, requiring the potential player’s careful consideration.

Final Thoughts

Stygian: Reign of the Old Ones accomplishes what many games fail, bringing to life the Lovecraftian. Unfortunately, this game falls short at the end and leaves game-breaking bugs as potential deterrents for full enjoyment. If what you read above entices you, it may be worth the investment. However, it’s unfair to recommend this game within its compromised state.

Gaming

Ashen (2018), a Game Review

Ashen (2018) is a souls-like action RPG developed by A44 and published by Annapurna Interactive available across all platforms.

Published

3 months agoon

April 30, 2024

Ashen (2018) is a souls-like action RPG game developed by A44 and published by Annapurna Interactive. This game provides a single-player and multiplayer experience with passive multiplayer mechanics. For this review, I am discussing the 39.99 Steam release, but it’s also available in the Epic Game Store, Xbox, Nintendo Switch, and PlayStation.

In this bitter world, your character seeks to make a home for yourself and others. This goal requires you to fight for every inch of land, building connections and alliances to maintain a thriving village. Venture further to make the world a more hospitable place, but know the further you travel, the greater the threats.

What I Like about Ashen

In 2017, Ashen earned a nomination for the Game Critics Awards’ “Best Independent Game.” It would later earn several more nominations in 2019. At the National Academy of Video Game Trade Reviewers Awards, it received nominations for “Game, Original Role Playing” and “Original Light Mix Score, New IP.” It was nominated for “Most Promising New Intellectual Property” at the SXSW Gaming Awards. Finally, at the Golden Joystick Awards, it earned a nomination for “Xbox Game of the Year.”

The multiplayer experience remains essential for Ashen, focusing on you and a partner venturing together to explore an open-world environment. However, the single-player experience is my focus and the game accounts for this gameplay. Ashen often pairs you with a villager who helps with the challenges.

The art style remains a plus throughout the gameplay. Though muted in colors and lacking finer details, the style creates a unique world that allows players to get lost along their journey. If the aesthetic doesn’t evoke that curiosity, then Ashen becomes hard to recommend.

Vagrant’s Rest and the inhabitants remain a strong incentive to continue on your journey. Seeing the progression of the town and building connections with the people provide the most rewarding experience.

In terms of horror, the art style often evokes an eerie atmosphere. However, I won’t go so far as to say the game is haunting. Instead, it evokes emotions that can unsettle and unnerve the gamer.

Thoughts and Considerations

The souls-like influence remains straightforward. Progression requires the player to defeat enemies and collect currency for weapons or certain item upgrades. Ashen simplifies and focuses its gameplay, reducing variety to polish its choices. The gameplay remains fluid, with a few hiccups that might be a computer issue.

If you prefer magic or defined classes, the gameplay doesn’t enable this variety. Item upgrades and choices define your playstyle, allowing most items to be playable at any stage of gameplay.

Weapons make a greater difference in playstyle. Most of these differences are self-evident (i.e. blunt weapons are slower but stun), but upgrades make any weapon viable. You pick an aesthetic and function, sticking with it until something better catches your eye.

What I Dislike about Ashen

As mentioned, the game had some technical issues. I often assume this to be my computer, but I did note a few others mentioning similar issues. The gameplay remains fluid, so take this comment as a small point of consideration.

With limited roleplay options, liking the characters or art style remains essential for your time and money investment. As mentioned, the game doesn’t hold the variety of FromSoftware, which means their selling point comes from that unique art style and world.

Passive multiplayer is a major part of the marketing for Ashen. While I don’t mind this mechanic, 6 years after release reduces the overall impact. When so few wanderers appear in your game, it’s hard to see the overall appeal.

Final Thoughts

Ashen delivers a highly specialized souls-like experience, preferring to perfect what it can at the cost of variety. If the art appeals and the thirst for a souls-like has you wanting, Ashen stands as a strong contender. However, there are many contenders which make this hard to overtly recommend.

Gaming

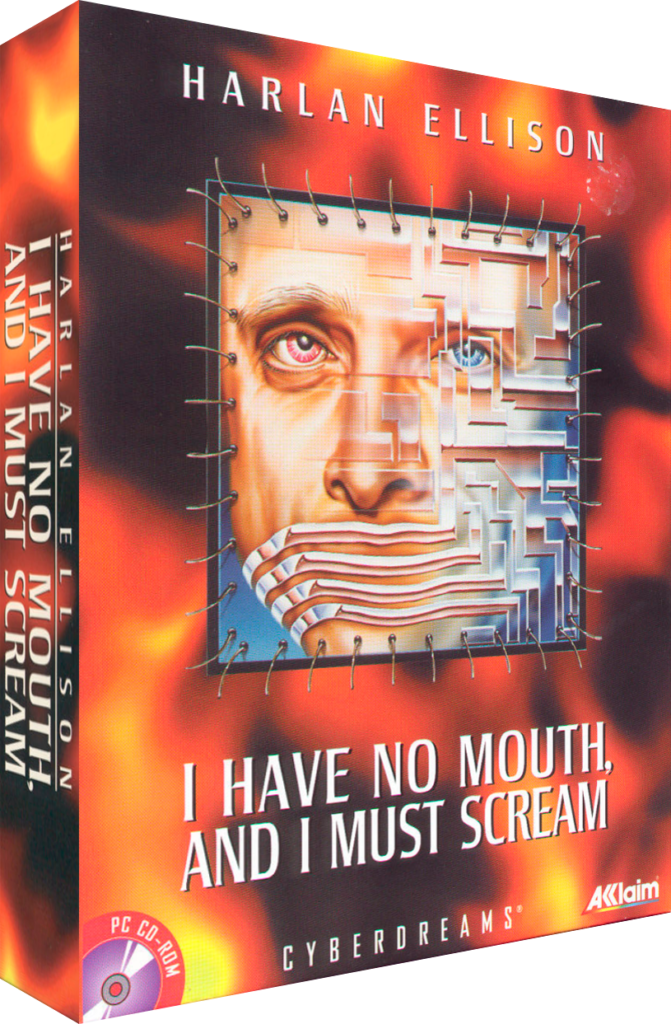

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream (1995), a Game Review

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream (1995) is a point-and-click horror game based on Harlan Ellison’s award-winning short story.

Published

3 months agoon

April 29, 2024

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream (1995) is a point-and-click horror game based on Harlan Ellison’s award-winning short story of the same name. Developed by Cyberdreams and The Dreamers Guild, this adaptation brings a new perspective to a familiar story. I heard of free purchasing opportunities for this game but cannot verify the quality. For this review, I played the 5.99 Steam release.

Play as one of the remaining humans on earth: Gorrister, Benny, Ellen, Nimdok, and Ted. Each faces a unique challenge from their common torturer, the AI supercomputer known as AM. Chosen by AM to endure torment, these challenges require the participants to face their greatest failures and tragedies.

What I like about I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream

Having experienced this story a few times, Harlan Ellison provides the most substantive execution of his vision and moral questions in this game. While all have individual merits, I assume the added content and context better dive into the relevant points he hoped to explore. He also played the voice of AM, giving us the emotional complexity of the machine as he saw it.

As the above comment indicates, I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream remains a faithful adaptation with only one notable change. While that one change does reflect in that character’s journey, it uses that opportunity to the fullest. Where the short story left room for potentially inaccurate interpretations of the characters, this added context makes us better understand them.

The game’s writing remains a selling point for this story-driven experience. It dives further into the lore of the human characters and even allows further development of AM in the process. There are many ways to progress, and the multiple characters allow gamers to adventure further if stuck. That said, progressing individual characters to complete their journey remains essential for the true ending and experience.

As a point-and-click game made in 1995, I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream holds up well. In many ways, it pushed the genre in its time with dynamic storytelling and game features. Harlan Ellison was someone who pushed boundaries to challenge himself and others. He saw the gaming industry as another opportunity to evoke story-driven art, a focus reflected here.

Thoughts, Triggers, and Considerations

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream adapts a dark and bleak story from an author notorious for his dark material. This game is no exception to that standard. Mental illness, sexual assault, genocide, and torture envelop the game. These elements are handled with attention but remain triggering to those sensitive to such dark material.

If these are deal breakers, I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream will likely earn a skip.

What I Dislike, or Considerations, for I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream

While the short story remains a haunting example of fiction in every sentence, I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream doesn’t evoke the same tension. It allows room to breathe or refocus on another character, which reduces the horror such a story evokes. While the characters participate in their torment, the loss of agency and hopelessness doesn’t translate in the execution.

Some mechanical and gameplay issues are noteworthy. For example, the saving mechanic remains dated, piling up if you save often or for specific reasons. Most of the mechanical issues stem from outdated UI from a gamer of a more modern era. Play it long enough, and elements start to click, but it needs that user investment.

Point-and-click caters to a niche audience, so modern gaming audiences aren’t inherently the demographic. The puzzle-solving and gameplay won’t win you over if the genre isn’t to your taste. Even within the genre, many of the puzzles remain challenging. For fans of the genre, this likely earns a positive merit. For those looking to continue the short story, this challenge will prove an obstacle.

Final Thoughts

I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream provides a new opportunity for the award-winning story to reach new audiences and continue to grow. Not satisfied with repeating his story in a new medium, Harlan Ellison expands this bleak world through the point-and-click game. While not as haunting as the short story, this game provides the most context and development of any adaptation before it.