Review: The Devil’s End by D.A. Fowler is an Eyeball Explosion at the very end

Trigger warnings: animal abuse and gore mentioned

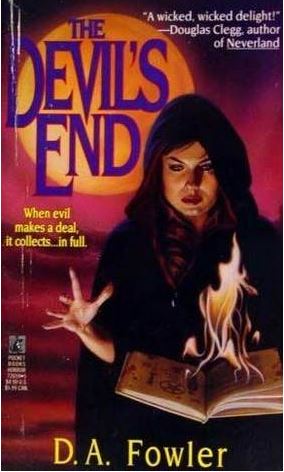

So, I wish that I had seen the original cover because that would have answered some of my questions. Not all of them, oh heavens no, but a good lot of them. Like, what time period are we in? I asked myself this over and over because it was unabashedly unclear. With references to Dick Tracy, Lana Turner, and MTV – it could be anywhere from the 1930’s to 1990’s (let’s get real, after the 90’s there really wasn’t an MTV anymore). With kids going to the corner store to get a coke and ride around town, it sounds like the 1960’s. But in one instance, it makes fun of the 1950’s, as if it were an era from a hundred years ago. It is both in the past and in the future. It is a paradox!

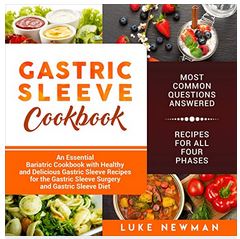

Oh wait, here’s the original cover:

Okay, great. Late 80’s, early 90’s – got it. Poof, I’m there. And I’m deducing that it was written by an older person because, again, a nine year old boy doesn’t know what the hell a Dick Tracy is in the late 80’s-early 90’s (trust me, no one saw that film and everyone who has has long since blocked it from their memory).

Oh, what, you want to know about the book? Oh, yes, I should review it since I read it. Or rather, listened to it, via Audible. This is the Audible cover:

I have to say, it doesn’t do it any justice at all. Even for a book that I’m about to give two Cthulhus to, it deserves the original cover because it explains the book so much better and is just a beautiful image. It primes you for what the book is truly about and what to expect – white people problems witchcraft.

The Plot:

There are a million characters, I’m going to narrow them down to three: Nancy, Lana, and Spiro.

Lana is the new girl in town, just moved from Texas after her mother’s messy divorce and work relocation. She is beautiful, but down-to-earth, and trying to find new friends while her mother resettles and her younger brother is a straight-up asshole. She is just the girl next door, literally.

Next door lives Spiro, a boy Lana’s age, with developmental and intellectual disabilities. He is shy, awkward, and horrendously bullied at school, regardless of his enormous stature. Growing up fatherless, his mother is cruel and archaic, punishing him for every imagined slight and then often neglecting him. He becomes infatuated with Lana, due to her kindness.

Nancy is a popular girl in the school, brash and unafraid of anything, she goes into the crypt one night of the local cursed family and finds a book. The local legends say that the family were witches and had sacrificed a baby to the devil for powers and immortality, and intrigued, Nancy begins to dabble with the book, to see if the rumors are true.

All three of their lives interweave when mysterious things around town keep happening – could Nancy be the cause of it? Or perhaps the family isn’t as dead as everyone thought?

Thoughts:

Okay, first off, the beginning 3/4ths of this book are pretty uninteresting; it’s mainly setting up “character” where there just isn’t any. As stated, there are so many characters that it’s ridiculous, even the parents of the kids are introduced, and then other characters are introduced half-way in. It’s a mess. Honestly, a lot of it could have been cut down and wouldn’t be missed.

To boot, all of the characters (except for Lana) are awful, insufferable people. It’s hard to listen to them when they are moldy garbage people who are just as interesting as the little bits of toilet paper stuck to the tp roll. Lana is constantly surrounded by young men who want to sexually harass her, her brother who literally wants to ruin her life, and the clique-ish girls at the school. But at the same time, it’s hard to identify with her because we’re constantly reminded how utterly smoking hot she is.

Most of the reviews I’ve read love the first part and hate the second, or never even get to the second. The “second” is the last 1/4th and was infinitely better because it went bawls-to-the-walls insane and gory. Fowler is actually very good at writing gore and, hoo boy, there needed to be 80% more gore and spooky and 120% less talking about nothing and getting Cokes at the burger shop.

The gore is mostly body horror, but there’s plenty of animal murder (which a lot of people found offensive by the comments I read) and…I’m not sure how to put this…gross baby-making-type stuff. You could find it vulgar, I mostly just found it erring on the side of sexist (and yes, I know this was a lady writer). Eyeballs do explode. I found that delightful. I also was entertained when a character’s naughty-bits started “spraying blood all over the living room like an unmanned firehouse”.

There are a few clever ideas that I won’t let spoil the story but, lightly, I think how some of the demons manifest and are different characters would have been more terrific if better explored and savored. I always find demons as characters interesting; unfortunately, these were the typical, standard issue demons, which is almost ironic because there’s a point when someone does a bit with The Exorcist, and then Fowler just kind of copies it later. It would have been great to set up the human characters in the first part, slowly trickle the demons in with their own personalities so that we’re acquainted with them, and then go to the climax of the story with everything mixed.

Honestly, I think this would have worked better as a short story or novella. There was too much fluff to get to where we wanted and needed to be.

Brain Roll Juice:

I’m going to get this out of the way first because it didn’t sit well and now that I have a timeline I can say, “Don’t give me ‘it was just different times’ bull-hockey.” It was, indeed, different times. Different, racist and sexist times. But before those fun times, let’s get to that other thing stuck in my craw – the treatment of Spiro. And I’m not talking about the kids in the book.

Spiro has some kind of developmental and/or intellectual disability, brought on from when his mother contracted German measles/Rubella and he, in utero, suffered from encephalitis (inflammation of the brain). He is seventeen, over six feet and two hundred pounds, and physically and mentally abused by his peers, teachers, and mother. He is in the same classes without additional support as his peers. He is punished with detention for “daydreaming”. He is called “’Tardo” and “freak” within earshot of teachers and authority figures. He is often physically abused by his mother.

He also turns into a disgusting creep and is painted in so broad and stereotypical a brush that I found it offensive.

From “gentle giant” stereotype to “creeper of the only nice girl to me” stereotype to “snapping from repression” stereotype to “spoiler spoiler spoiler” stereotype. There isn’t anything clever or sincere about the character and that chips my paint. He is the only diverse character in the whole bunch and he has absolutely nothing of substance to say or do. I was furious because I was excited to see a rare neuro-diverse character in horror as, what I thought, was a lead role (the first chapter starts with him – he introduces the story), or at least a sympathetic role.

And no, that ending doesn’t factor in. Without going into details, let’s just say that his send off was very similar to the classic moment in TV history:

The same sentiment can be said with the wildly racist comments that drop out of flipping nowhere, like, “that’s why Japanese people’s eyes are slanted…all the books they read”, “Is an African’s hair kinky?” (used like “does a bear sh– in the woods?”), and “ghetto blaster” as a sobriquet for a boombox. Or the introduction to the only black character at the end of the book that actually calls his peers, “chillun”.

Poor Michael Reaves, the narrator, for having to cough out these lines and make the best out of it. He’s even had to narrate a gastric sleeve cookbook and probably had a better time with that.

But let’s take a look back – this was published in 1992. The year that Dr. Mae Jemison became the first African American woman to travel into space; that the Kentucky Supreme Court held that laws criminalizing same-sex sodomy are unconstitutional (and accurately predicted that other states and the nation would eventually rule the same way); and a TWO full years after Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 was signed into law.

So, what am I saying? I’m saying that you’re right. The times were different and changing. This book has aged and will continue to do so. Even if this is just a pulp horror novel, it’s also a time capsule. I can read this and watch a movie like “Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark” and see how far our narrative focus has changed. Call it SJW-appeasement or diversity-pandering, but it has changed. It’s no longer just 311 pages filled with average high school melodrama with occasional exploding eyeballs, but showing new facets from new perspectives to keep the same stories we keep telling each other fresh and engaging to more people.

And that leads me to wonder, what would these characters look like now? How would we react to them? How would they change the narrative if they were written today? And do people even know who Dick Tracy is anymore?

Bottom-line:

If you like gore, it’s drudgery to get through the first part. If you like character development, there isn’t much of any. If you like late-80’s to early-90’s nostalgia…I’d still advise against it. It’s not great and aged even worse.

(2 / 5)

(2 / 5)

Book Reviews

A Stellar Debut Novel, We Used To Live Here

Imagine this. You’re home alone, waiting for your partner to return, when you hear a knock on your door. You answer it to see a family of five, bundled up against the cold. The father, a kindly older gentleman, explains that he used to live in this house as a boy. And he would love to show it to his family.

Do not let them in.

The story

Released in June 2024, We Used To Live Here is author Marcus Kliewer’s debut novel. It tells the story of Eve, who just purchased a beautiful house with her partner, Charlie. Their plan is to flip the house and sell it.

One night, while waiting for Charlie to come home, Eve is surprised by a knock at the door. It’s a man named Thomas Faust and his family.

Thomas explains that he grew up in the house and hasn’t been in the area in years. Would Eve let them in so that he can show the home to his children?

Against her better judgment, Eve lets them in. She regrets this almost at once when Thomas’s daughter vanishes somewhere into the house.

What worked

I always appreciate a book that allows you to play along with the mystery. And this book does that better than just about any other I’ve seen.

Pay close attention to the chapters, to the words that aren’t there. To everything about this novel.

This is mostly down to Kliewer. This is ultimately his work of art. But the production value is also fantastic. I don’t want to ruin the multiple mysteries, so I’ll just say this. There are clues in this book that require some specific artistic choices in the page layouts in this book. And I loved that.

If you’d like to experience another horror book review, check out this one.

We Used To Live Here is also the kind of story that makes you question everything right along with the main character, Eve. Eve is a great main character. But she might be an unreliable narrator. She might be experiencing every single horror described, exactly as it’s described. Or, she might be having a psychotic breakdown. Through most of the book, we can’t be sure. And that is so much fun.

Finally, the weather plays a large part in this story. There are several stories in which the weather or the land itself could be considered a character. Even an antagonist. This is certainly one. The winter storm is the thing that traps the family in the house with Eve. It also makes escaping the home difficult. Reading this book during the winter was especially impactful. Most of us know what it feels like to be shut in by a storm. I’ve personally lived through some of those storms that are just referred to by their year, as though they were impactful enough to claim the whole 365 days for themself. And that was with people I liked. Imagine what it would feel like with strangers. It’s a staggering thought and one that we explore in depth in this book.

In the end, We Used To Live Here is a fantastic book. It’s the sort of story that sneaks into your brain and puts down roots. And if this is just the first book we’re getting from Kliewer, I can’t wait to see what else he comes up with.

(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

Book Reviews

Exploring real terror with The House of My Mother

As a disclaimer, this is a review of The House of My Mother from a critical perspective. I will not be discussing my opinions of the legal case against Ruby Franke and Jody Hildebrandt. I will be discussing the merits of the book as a work of true crime alone.

In 2015, Ruby Franke started a YouTube channel called 8 Passengers. In August of 2023, Franke and her business associate Jodi Hildebrandt were arrested for, and later plead guilty to, charges of aggravated child abuse. And in January of this year, Shari Franke told her story in The House of My Mother.

The story

The House of My Mother is the true story of Shari Franke, the oldest child of one of the most famous family vlogger families.

As a child, Shari came to the conclusion that her mother didn’t like her. Soon, she began to fear her mother’s anger.

Things got significantly worse when Ruby started their family vlog. All of the families most intimate moments were splashed across the internet for anyone to watch. This became a living nightmare for Shari.

Of course, that was only the start of the family nightmare. Because Ruby was about to meet someone who would reinforce all of the darkest parts of herself.

Eventually Shari manages to escape her home. But her younger siblings were still in her mother’s clutches. She had to save them, and her father, from the monster her mother had become.

What worked

Through the book, Shari only ever mentions the name of one of her siblings, Chad. This is because Chad is the only of her siblings that is an adult at the time of the publication.

There are children involved in this story. Children who’s lives and privacy have already been damaged. Shari didn’t want to do that to them again, and neither do I.

It probably won’t surprise you that this book is full of upsetting details. But not in the way you might imagine.

Nowhere in this book will you find gory details about the abuse the Franke kids suffered. And I consider that a good thing. Those sort of details are all fun and games when we’re talking fiction. When it’s real kids who are really living with the damage, it’s not a good time.

What you’ll find instead is a slew of more emotionally devastating moments. One that stuck with me is when Ruby’s mother gives her a pair of silk pajamas as a gift after Ruby gave birth to one of her babies. Shari asks Ruby if she’d bring her silk pajamas when she had a baby. Ruby responds that yes, when Shari becomes a mother they can be friends.

What a lovely way to make a little girl feel like she’s not worth anything unless she reproduces. And, if she does decide to have children, who is going to bring her silk pajamas?

In the end, this isn’t a story about ghosts or demons. It’s not about a serial killer waiting on a playground or in the attic of an unsuspecting family. Instead, this is a story about things that really keep us up at night. It’s the story of a woman so obsessed with perfection that she drove away her eldest daughter. The story of a young woman who’s forced to watch from afar as her beloved brothers and sisters are terrorized and abandoned. These are the sorts of things that really keep us up at night. These are the real nightmares.

More than that, though, The House of My Mother is a story of survival. It’s about a family that was ripped apart and somehow managed to stitch itself back together again. It’s about a brave young woman who managed to keep herself safe and sane in the face of a nightmare. If you haven’t read it yet, I can’t recommend it enough.

For more like this, check out my review of Shiny Happy People.

(5 / 5)

(5 / 5)

Book Reviews

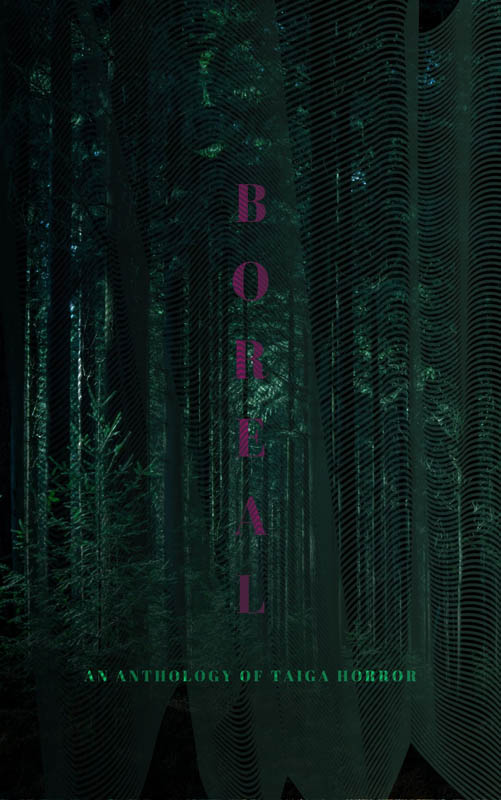

Book Review of Boreal: an Anthology of Taiga Horror

Boreal: an Anthology of Taiga Horror is a collection of twenty-two haunting tales that dwell in the deepest darkest woods and frozen wastelands, edited by Katherine Silva and including Haunted MTL’s very own Daphne Fauber. Each story has even been gifted with its very own poster, hinting at the horrors to be found within it, bestowing a beautiful visual collection as well.

The tales are varied and touch upon the environment in new and different ways, each hearkening to a sort of epiphany or raised awareness. These stories exude both dread and wonder at the smallness of our human existence in contrast to the sacred world we have isolated from, sheltering ourselves in our comfortable houses with centralized heat and everything we could possibly need or want at the ready. The taiga becomes a sanctuary outside of our own dulled awarenesses. It is a holy place imbued with powers beyond mortal human reach, a wilderness that threatens to swallow us – both whole and bit by bit, simultaneously.

The protagonists enter into this realm through ritual, superstition, longing, stubbornness, and their own hubris – yearning to survive its dangers, and to make their own marks upon it. The starkness of their surroundings harbors delicate moments that would be all too easily missed if not deliberately sought or pointed out. The softness of fur, the dappled sunlight shining through trees, the hazy clouds of breath forming in crisp air, the brittleness of bleached bone… those quiet experiences that beg to be forgotten, to lay safely sleeping just below the frozen surface, awaiting spring.

There are those who followed in the footsteps of their predecessors, seeking to escape the constraints of their parent’s and elders’ indoctrination, traditions, madness, and abuse, yearning to find their own way despite also being inextricably bound to their own pasts. There are those who just wanted to go for a walk in the woods, and remained forever changed by what they experienced. There are those who wished to impose their will upon the wilderness, their order falling to disarray, unable to make lasting impact. There are those who sought to leave behind the world of mankind, looking for oneness in the natural order of things through isolation, leaving a bit of themselves behind after being consumed by the terrors they encountered. There are those who truly found communion with the woods, became one with its wildness, and invited its spirit into their hearts to find peace, even at cost of their own lives. And then, there are the spirits themselves…

(3 / 5)

(3 / 5)

All in all, I give Boreal: an Anthology of Taiga Horror 3.0 Cthulhus. I love existential angst so I found it to be an enjoyable read, and I appreciated the myriad manners in which the biome was explored. But there were points in which I found myself struggling to follow along, as if the words were swept up into their own wilds in ways that alienated myself as reader, as if my mere voyeurism into this otherworldly place was not enough to comprehend the subtle deviations in storytelling mannerisms fully. I suppose in some sense this seems appropriate, but at the same time, it left me feeling a bit unfulfilled, as if I had missed a spiritual connection that should have resonated more deeply.